Forward: why we write

Writing your first manuscript is intimidating. It’s hard to know when you’re ready to start writing, and how to begin the process. My first draft took a month. I had anxiety: What if my results aren’t significant enough? What if I’ve made a mistake in the analysis? What if, after all this effort, the journal I’ve chosen rejects me? In hindsight, those weren’t the right questions to be asking.

So, before you read on, we need to talk about why we write. Scientific manuscripts began informally in the late 1600s in the form of short letters, as way to disseminate scientific knowledge. While we have adopted a more formal peer-review since then, we publish today for primarily the same reasons: to communicate scientific findings and to teach others.

Most of us will never write the “gold standard paper” whose results and interpretations survive the test of time completely intact. Science is incremental; rarely does it progress on one article’s evidence alone. In the end, we write to contribute to a much larger scientific discourse, from which a single question is answered after years of scientific evidence generated from multiple labs by hundreds of hard-working researchers.

We do our best to ensure we’ve been rigorous in our analyses and conclusions. But as one author rightly put, experimentally solid papers are timely, targeted, and temporary.1 We try to publish results that are relevant to current topics in our field, knowing that there will be limits to its application and scope, or that the conclusions from these results are subject to revision and reinterpretation.

We also write to teach ourselves. Scientific writing is as critical to our scientific training as the science itself. In writing, we learn to re-formulate our hypothesis; we frame old topics in new ways. Each new piece of data causes us to revisit prior assumptions. In the end, writing is a marathon, not a sprint.

Part I: Defining your story

Figure outlines structure your story

So how do you know when you’re ready to start writing? And what constitutes publishable content? Generally, you want to start writing when you’ve collected 80% of the data. Never start writing after you’ve collected all the data. Scientific writing is as critical to our scientific training as the science itself. Writing helps you realize the gaps in your data. You might realize that you can’t make the claim you want without additional experiments. That said, there’s plenty to do before putting pen to paper. A solid story is the foundation of good scientific writing. That’s where figure outlining is your friend.

Start a figure outline early

It’s never too early to start figure outlining. No data? No problem. Figure outlining is a visual tool for helping you decide the most critical experiments you need to perform in order to test your hypothesis. Ultimately, it’s your blueprint for writing a paper.

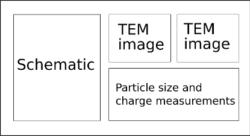

Most journals have 5-6 medium-sized figures with several panels. Do some research on the kind of data your field typically reports by looking at journals from your lab. Do they start by characterizing the materials? Describing the system they used? Don’t be afraid to put placeholder “boxes” for data you don’t yet have. Generally, 1 figure = 1 experiment. Your figure outline should include the 5-6 major experiments that drive your hypothesis.

Outline to inform your experimental approach

As you continue to collect data, you may need to shift your story. You’ll refine your hypothesis until you’ve settled on a main story. Ultimately, that story may look very different from your initial expectations. This is part of the scientific process. As an experimentalist, one way I try to help define structure early-on is by prioritizing a few key experiments that can help me decide the central message of my story. Think about your hypothesis: which main experiment would be highlighted in a paper to support such a hypothesis? Of course, this research would need to be supported by multiple experiments. But most papers have one key figure that summarizes the key results. Your PI should be able to offer suggestions if you’re having difficulties with this.

Example: I work in cancer nanotechnology, and the biggest challenge for me is animal experiments. These are costly and time-intensive, so there is a lot of pressure to collect meaningful data. Unfortunately, this is also the type of experiment that ultimately decides the fate of the story I tell. I’ve found that the sooner I start these experiments, the easier it becomes to tell a meaningful story. These experiments then drive the design of smaller experiments I run to support my hypothesis.

Use outlining as an organizational tool

Writers outline to organize their thoughts. Scientific writers similarly require high-level organization to ensure flow. For experimentalists, it might be several years before you generate enough data for a complete story. Keeping a figure outline with all your data keeps you organized. It helps you re-visit old experiments and generate new hypotheses. That also means it needs to be constantly updated and re-worked. In this stage, when things are more fluid and subject to change, it can feel time consuming to constantly re-do old outlines. Don’t be afraid to jot down your thoughts in a bullet outline if it’s more conducive to getting your thoughts down quickly. However, bear in mind that figure outlines can help you visualize the data in ways that a regular outline cannot. If you’re planning on providing graphical data, what are your x and y axes (what do you hope to measure experimentally)? If you’re characterizing a material you made, what data will go into the main figure as opposed to the supplemental information? This can help you prioritize what characterization data you should be collecting first.

![]() Tip: As soon as you generate new data, make a figure for it and add it to a powerpoint or word document. It will help you stay organized, remind you of old data, and help you re-work your hypothesis and plan for future experiments.

Tip: As soon as you generate new data, make a figure for it and add it to a powerpoint or word document. It will help you stay organized, remind you of old data, and help you re-work your hypothesis and plan for future experiments.

I have my figure outline. I’ve collected the data. Now what?

So you’ve finally filled most of your outline with data. You have a story. How do you know when you’ve collected 80% of the data? How do you know when you’ve made a significant contribution to the field? Can you start writing?

The truth is, this is largely a judgement call. Ultimately, it often comes down to how specific of a claim you’re making and the journal you’re aiming for. The more specific your claim, the narrower the audience, and, in general, the lower the journal impact factor. The more general the claim, the broader the audience and the higher the impact factor. The more specific your claim is, the less evidence you’ll need to support it. For example, you’ll need far less evidence to assert that X performs with optimal precision under conditions Y, Z and Q, than if you were to say that X performs optimally in all cases and therefore everyone in the field should use it.

What you deem a publishable unit also depends on personal factors: Are you graduating and in need of paper? Maybe you don’t care about impact factor and prefer to publish sooner. Maybe collecting that extra set of data will allow you to publish in a higher-impact journal. Then again, maybe you don’t have the time to go through a lengthy review process before funding dries up. It’s worth noting here that the goals of your PI (e.g. to publish in high impact, visible journals where they will be cited) might not always align with your personal goals (e.g. to leave with several publications before graduating). Keep in mind that the quality of a journal article is only loosely correlated with the impact factor of the journal it’s being published in. What is correlated, however, is the length and difficulty of the review process. Higher impact journals demand a higher level of data collection and analysis; the standard for what constitutes a publishable unit is, in theory, much higher.

![]() Tip: How do I know what a standard publishable unit is for a specific journal? Look up the latest articles published by that journal in your field. What kind of data have they collected? Don’t forget to check the supplemental!

Tip: How do I know what a standard publishable unit is for a specific journal? Look up the latest articles published by that journal in your field. What kind of data have they collected? Don’t forget to check the supplemental!

Part II: Finding the right home for your work

Finding the right journal to publish your work takes time and research. If this is your first time publishing, give yourself time to explore different options and weigh the pros and cons of publishing in each. Keep in mind that this might be the first time you’re thinking seriously about the peer review process—factor in time to do your homework. You need to research how to publish your research.

Narrow your focus

Concentrate on researching a small group of journals in your related field of work. The most obvious first step is talking to your PI. Some PIs prefer your work to be published in a very specific journal or family of journals. Others will leave it completely up to you. Regardless of your specific situation, your PI should always be your first source when asking for journal recommendations.

If you find yourself needing additional advice, talk to senior members of the lab who know the contents of your story well enough to advise you on where to publish. You should also have a conversation with other members of the authorship team that have experience in selecting journals.

Lastly, you can always do your own research: Where has your lab published before? Unless your professor is brand-new, your lab should have a list of publications. Scan the list and keep track of where similar work has been published before. At some point, you’ll have accumulated a substantial list of references in a citation manager. Scan your library for where similar content has been published.

Research the journal

Scope and fit

Most journals will have a page on journal scope in their About section. This is a great way to quickly find out whether your article is a good fit. I’ve found that some journals do a better job of this than others. High impact journals will be vague about what they’re looking for. For these journals, you’ll need to decide whether your story is “novel enough”. It can be especially difficult to decide where to publish if your work is highly interdisciplinary. In these cases, you’ll want to think about other aspects of the journal like the style, tone, and readership discussed more below .

In select cases, it may be beneficial to have your PI submit a letter of interest to the editor, along with an abstract of the work. Some journals put out a call for papers from a specific area. If your work falls fits the call, you may have a higher chance of getting your paper accepted.

Style and tone

Even if you think your research falls within the scope of the journal, you’ll need to consider whether it matches its style and tone. Some journals having a “teaching element” to them: they seek to describe a basic fundamental finding. Other journals have an “applied” focus. As engineers doing research, we often fall into one of two categories: (1) basic science research that explains a fundamental concept (2) solutions generated to address specific challenges.

![]() Tip: Look up the latest papers that journal has published in your field. How do they describe their research? Pay attention to how they set up and address challenges in the abstract, intro, and discussion, as well as the vocabulary they use to describe the novelty of their research.

Tip: Look up the latest papers that journal has published in your field. How do they describe their research? Pay attention to how they set up and address challenges in the abstract, intro, and discussion, as well as the vocabulary they use to describe the novelty of their research.

Readership

Consider who the interested audience is. Is it an entire field? A subfield? Someone who uses a similar system? Journals range from very broad (Science, Nature) to very specific (Langmuir, Soft Matter). Consider which audience would benefit the most, or would be most interested, in reading about your research. Also consider the impact of your main message on the broader community—who are you seeking to reach?

If you’re interested in pursuing academia, it might also be important to consider the subfield you’re interested in becoming an expert in, and how journals are ranked in those areas. While Nature and Science might have high impact factors, most academics in chemistry would rank published pieces in JACS – (Journal of the American Chemical Society) far higher in terms of quality and thoroughness of research.

Lastly, know what types of manuscripts the journal accepts and the page and figure limitations. If you’re looking to publish a full research article, and a journal only accepts briefs, short letters, or communications, look elsewhere to publish your research.

Practical considerations

Keep in mind how the publishing process will fit into your short and long-term goals. Are you trying to graduate soon? How long is the typical review process for this journal? For high-impact journals like Nature and PNAS, the process can take up to 6 months. Some tools like SciRev exist for this purpose.

Variations in the manuscript-writing process

It’s difficult to come up with a one-size-fits-all process to manuscript writing. PI preferences and lab culture vary. Your experience may not happen in the exact sequence outlined above, but it will have all the components. That said, it’s important to have early discussions with your PI during drafting process. Talk to them about their expectations and level of involvement. Some PIs only want to see the final draft of a paper—others may want to see every iteration of your figure outline.

Some PIs prefer to select a journal before conducting research, so you can collect the data with the journal and field in mind. If your PI hasn’t given you any guidance on what journal to select, and this is your first manuscript, this will be very difficult for you to do. Selecting a journal is an art perfected with practice research is unpredictable, and results may ultimately vary from preliminary predictions. Even if your journal is predetermined, it’s always worth revisiting whether the research still fits this publication, once you’ve collected that data.

Manuscript writing is intimidating, but it doesn’t have to be. Breaking the process into concrete, actionable steps, will help you organize your thoughts and make it easier to make incremental gains in publishing your research. See our follow-up blog post for tackling the next phase.

- Walbot, V., Are we training pit bulls to review our manuscripts? Journal of Biology 2009, 8 (3), 24.

Stephanie Kong is a graduate student in the Hammond Lab and a ChemE Communication Fellow.

Blog tags: #manuscripts101