The rise of ChatGPT and other AI tools has forced educators to respond with updated teaching and assessment strategies at MIT and across the globe [1, 2, 3]. As a graduate student and AI novice, my response to these tools was more curiosity than panic. These new tools seem to promise more efficient paper drafting, literature searches, and problem-solving, but the more time I spent querying ChatGPT, the less confident I felt in determining how and if AI should have a place in my research workflow. So, I set out to learn about these tools, understand their limitations, and test them for several research tasks.

Here I’ll share my journey and zoom in on the two tools I found to be most useful, ChatGPT and Elicit. Like any dutiful researcher considering a new experiment, I will focus on the key questions: Is this effective? and is this ethical? Whether you are an AI novice like me or keep a dedicated browser open for ChatGPT, I encourage you to join me in wrestling with these questions as you consider how to use AI tools responsibly in your research.

Is this effective?

ChatGPT

ChatGPT is a language processing tool powered by a machine-learning-based large language model (LLM). In other words, ChatGPT creates human-sounding responses to the prompts posed to it by essentially performing language regression, predicting which words are most likely to be associated with each other [4]. In practice, this means that ChatGPT can write a grammatically coherent essay, but through the quirks of probability, it might hallucinate the facts that make up the content.

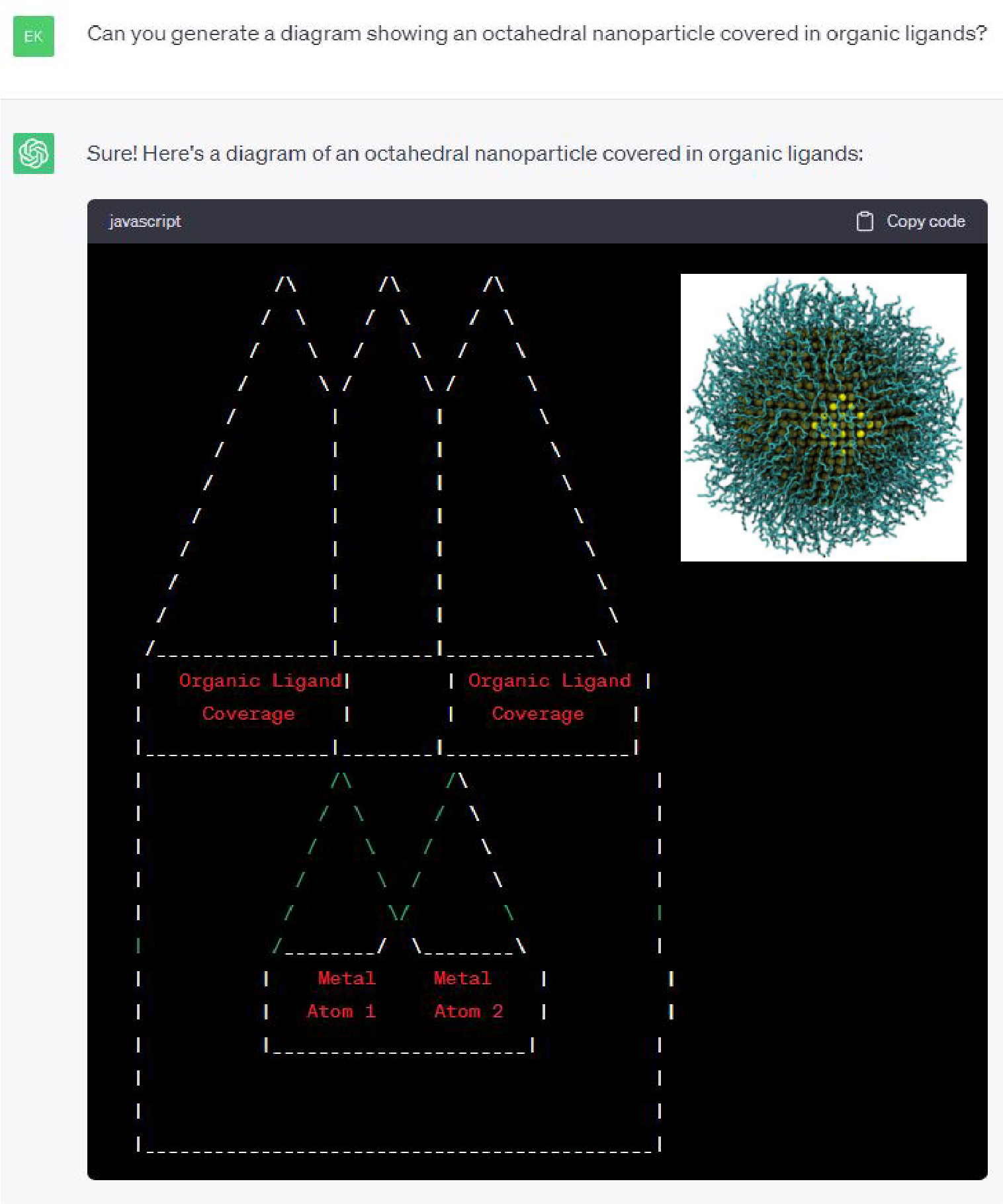

This hallucination appeared early on in my experimentation with ChatGPT. When I asked how ChatGPT can help me communicate science, one suggestion it gave was generating “visual aids such as graphs, diagrams, and infographics.” A follow-up query asking for a visual aid related to my research resulted in the JavaScript beauty shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. ChatGPT claimed that it could generate scientific diagrams. The main figure shows its take on a nanoparticle covered in ligands. The inset (top right) shows a published figure for reference. [5]

Although I certainly won’t be using ChatGPT to make figures anytime soon, I found it much more effective for other research tasks. Table 1 summarizes my experience using ChatGPT to brainstorm analogies, simplify language, write an email, translate code, and write a paper introduction.

Table 1. Summary of ChatGPT’s strengths and weaknesses for various research tasks

Research Task |

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

| Brainstorm analogies for my research | Can give you a ton of ideas (with varying coherence) if you continue to generate new responses. | Often didn’t make sense beyond the surface level but with some human tweaking could be effective. Does this stifle human creativity too much? |

| Translate a technical abstract into clear language for a general audience | Did a surprisingly good job of understanding and distilling jargon and organized the abstract nicely. | The content required some tweaks, but for an initial draft, I was pleased. |

| Write my advisor an email | If you’re really stumped on how to start an email, this could be a starting point for the email structure. | The email was long (good luck getting your advisor to read 5 paragraphs for a simple question) and weirdly formal. Even after iterating on tone, I was better off writing the email myself. |

| Translate code from MATLAB to Python | Successfully translated the logic of a simple code to upload, process, and plot data. | Struggled to capture the syntax for tasks such as reading a table, taking user input, and formatting a figure. |

| Explain why my research is important (such as what you’d find in the introduction of a journal article) and cite references | The text is clearly written and structured well. An effective strategy could be to keep the structure but incorporate your own content. | Most of the content is vague, and one statement that a process has been “studied extensively” is blatantly false. Four of the five citations do not exist. |

My early experimentation showed that ChatGPT cannot be trusted to give factual information, even about its own capabilities. Instead, I found that ChatGPT performs best on tasks where you provide the content up front or heavily revise the AI response. In my opinion, ChatGPT is most effective as a tool for writing synthesis and organization, but however you choose to use ChatGPT, the key is validation. Any claim that you want to make in a piece of writing should come from you.

Elicit

Elicit is an “AI research assistant” with the primary functions of literature review and brainstorming research questions. It interprets and summarizes scientific literature using LLMs, including GPT-3, but unlike ChatGPT, Elicit is customized to stay true to the content in papers. Even still, the company FAQs estimate its accuracy as 80-90% [6].

Since Elicit is a more targeted tool than ChatGPT, using it effectively requires an organized workflow. My typical method to perform a literature search with Elicit is

- Ask a research question.

- Star relevant papers and hone results with the “show more like starred” option.

- Customize paper information beyond the default “paper title” and “abstract summary” options. My favorite headings to add were “main findings” and “outcomes measured.”

- Export search results as a CSV file.

Table 2 shows a summary of my experiments using Elicit to perform a literature review and explain my paper .

Table 2. Summary of Elicit’s strengths and weaknesses for various research tasks

Research Task |

Strengths |

Weaknesses |

| Provide papers for a literature review | Eventually found all the papers I know of on a specific topic after several rounds of iteration, plus a few extras. | Works best when you pose your prompt as a question rather than as keywords. This took me some time to get used to and isn’t amenable to all search types. |

| Explain my paper to me through the “detailed abstract summary,” “main findings,” and “outcomes measured” options | Content is pulled directly from the paper and contextualized correctly. | There is some content missing that I would have included if I were summarizing these categories. |

Unlike ChatGPT, most information that Elicit serves up is true to the cited sources. However, its results still need validation since the information it pulls can be incomplete or misinterpreted. For this reason, I am most comfortable using Elicit as an initial screening tool, and I definitely recommend reading the papers before citing them in your own work.

Is this ethical?

There is no easy answer to the question of the ethics of AI, as evidenced by the tons of academic papers and op-eds already published on the topic [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. In my own thinking about AI and scientific research, the ethical facets which stood out to me the most are privacy, plagiarism, bias, and accountability.

Privacy and plagiarism

Did you know that the prompts you enter in ChatGPT are fair game to use in training the LLM? Even though OpenAI now provides a form allowing you to opt out of model training, many have flagged this as a serious privacy issue [13].

Imagine using ChatGPT to revise an initial paper draft. Should you worry that parts of your unpublished work may be served up to another user who asks about the same topic? On the other hand, imagine you ask ChatGPT to write part of your paper and, in doing so, unknowingly plagiarize other papers in the field.

The root issue of both scenarios is a lack of transparency in the LLM powering ChatGPT. Unlike emerging open-source language models, OpenAI does not provide public access to the GPT training data [14]. Yet even if it did, understanding the origin of model-generated content is not straightforward. If ChatGPT trains on your unpublished paper, that simply translates to a change in the numeric parameters of the LLM producing its responses. According to OpenAI, the model does not actually “store or copy the sentences that it read[s].” [4]

This seems to make explicit plagiarism less likely, but when it comes to the inner workings of these models, there is a lot we as users don’t know. Is it still possible for ChatGPT to plagiarize its training sources through a coincidence of its algorithm? Does this become more likely when you are in a niche field with less training data, such as a research topic for a Ph.D. thesis?

Bias in many forms

If you peel back the layers of ChatGPT, you’ll find a hierarchy of well-documented bias [15, 16]. As a researcher, the categories I worry about the most are sample, automation, and authority bias.

Sample bias is inherited from the counterfactual, harmful, or limited content in the training data of LLMs (e.g. the internet). For research applications, sample bias is most apparent in ChatGPT’s limited knowledge of the research literature. For example, when asked to summarize the work of several researchers, ChatGPT was only able to give accounts for some scientists, failing to produce any information about even highly renowned researchers [7]. Elicit may do a better job of this, but its content is still limited to the Semantic Scholar Academic Graph dataset [6, 17].

On the other hand, automation bias comes from how we choose to use AI tools and, specifically, when we over-rely on automation. Completely removing the human element from our research workflows can result in a worse outcome. Relying too much on automated AI tools for research tasks might lead us to reference hallucinated citations from ChatGPT, skip over key literature missing from Elicit’s dataset, or forgo human creativity in communication in favor of ChatGPT’s accessible but formulaic prose.

A closely related concept is authority bias, when we cede intellectual authority to AI, even against our best interests and intuition. Both my experiments and others highlight the weak points of AI’s knowledge and capabilities. As it stands today, AI isn’t actually that smart and does not deserve our intellectual deference [18].

These layers of bias highlight the need for clear guidelines on personal and professional accountability when using AI tools in research and scientific communication.

Accountability

In response to the growing use of AI tools, many journals have released statements on how AI may be used for drafting papers. The Nature guidelines are: 1) ChatGPT cannot be listed as an author on a paper and 2) how and if you use ChatGPT should be documented in the methods or acknowledgment sections of your paper [19]. Ultimately, you and the other human authors bear the full weight of accountability for the content of your paper.

In my opinion, both the weight of accountability and the inherent black-box nature of ChatGPT should make us cautious about how we use AI in scientific communication. The best way to protect against plagiarized, biased, and hallucinated content is to avoid relying on AI for content generation.

How do we move forward?

So what is an effective, ethical way to use AI to help with research tasks? Personally, I err on the side of caution, limiting my use of ChatGPT to the synthesis and revision of human-provided content and my use of Elicit to the beginning stages of a literature review. My methods aren’t right for everyone, though. How you choose to use AI should be determined by your ethical compass as well as the guidelines of your PI and research community.

No matter your comfort level, the best advice I can give for using AI tools in your research is to be transparent in how you use AI and validate AI content wherever possible. Ultimately, the best way to build AI into your research workflow is to experiment with it yourself, keeping in mind these core questions of effectiveness and ethics as you go.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to EECS Communication Lab Manager, Deanna Montgomery for sharing her framework on evaluating ethics and efficacy in AI.

References

[1] K. Huang, “Alarmed by A.I. Chatbots, Universities Start Revamping How They Teach,” The New York Times, 16 January 2023. [Online].

[2] D. Nocivelli, “Teaching & Learning with ChatGPT: Opportunity or Quagmire? Part I,” MIT Teaching + Learning Lab, 12 January 2023. [Online].

[3] D. Bruff, “Teaching in the Artificial Intelligence Age of ChatGPT,” MIT Teaching + Learning Lab, 22 March 2023. [Online].

[4] Y. Markovski, “How ChatGPT and Our Language Models Are Developed,” OpenAI, [Online]. Available: https://help.openai.com/en/articles/7842364-how-chatgpt-and-our-language-models-are-developed#h_93286961be. [Accessed 7 June 2023].

[5] S. W. Winslow, W. A. Tisdale and J. W. Swan, “Prediction of PbS Nanocrystal Superlattice Structure with Large-Scale Patchy Particle Simulations,” The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, vol. 126, pp. 14264-14274, 2022.

[6] “Frequently Asked Questions,” Elicit, [Online]. Available: https://elicit.org/faq#what-are-the-limitations-of-elicit. [Accessed 7 June 2023].

[7] E. A. M. v. Dis, J. Bollen, W. Zuidema, R. v. Rooij and C. L. Bockting, “ChatGPT: five priorities for research,” Nature, 3 February 2023. [Online].

[8] E. L. Hill-Yardin, M. R. Hutchinson, R. Laycock and S. J. Spencer, “A Chat(GPT) about the future of scientific publishing,” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, vol. 110, pp. 152-154, 2023.

[9] D. O. Eke, “ChatGPT and the rise of generative AI: Threat to academic integrity?,” Journal of Responsible Technology, vol. 13, p. 100060, 2023.

[10] B. Lung, T. Wang, N. R. Mannuru, B. Nie, S. Shimray and Z. Wang, “ChatGPT and a new academic reality: Artificial Intelligence-written research papers and the ethics of the large language models in scholarly publishing,” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, vol. 74, no. 5, pp. 570-581, 2023.

[11] R. Gruetzemacher, “The Power of Natural Language Processing,” Harvard Business Review, 19 April 2022. [Online]. Available: https://hbr.org/2022/04/the-power-of-natural-language-processing.

[12] M. Hutson, “Could AI help you to write your next paper?,” Nature, 31 October 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-03479-w.

[13] “User Content Opt Out Request,” OpenAI, [Online]. Available: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLScrnC-_A7JFs4LbIuzevQ_78hVERlNqqCPCt3d8XqnKOfdRdQ/viewform. [Accessed 7 June 2023].

[14] E. Gibney, “Open-source language AI challenges big tech’s models,” Nature, 22 June 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-01705-z.

[15] B. Cousins, “Uncovering The Different Types of ChatGPT Bias,” Forbes, 31 March 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2023/03/31/uncovering-the-different-types-of-chatgpt-bias/?sh=4dcf52fc571b.

[16] H. Getahun, “ChatGPT could be used for good, but like many other AI models, it’s rife with racist and discriminatory bias,” Insider, 16 January 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.insider.com/chatgpt-is-like-many-other-ai-models-rife-with-bias-2023-1.

[17] “Semantic Scholar API – Overview,” Semantic Scholar, [Online]. Available: https://www.semanticscholar.org/product/api. [Accessed 7 June 2023].

[18] I. Bogost, “ChatGPT Is Dumber Than You Think,” The Atlantic, 7 December 2022. [Online].

[19] “Tools such as ChatGPT threaten transparent science; here are our ground rules for their use,” Nature, 24 January 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-00191-1.

Eliza Price is a graduate student in the Tisdale Lab and a ChemE Communication Fellow.