When sharing our research with others, we are expected to provide context, explain our findings, and assist in interpretation of data, all while carefully considering the audience, goals, and progress of projects. On top of that, we want to choose the right presentation to deliver the message in a compelling, engaging, and credible manner. This blog post is a guide to help you determine the appropriate strategy to accomplish all of these goals. While we mainly focus on presentations, the same framework of developing a clear narrative supported by evidence can be generally applied to any of your communication needs in BE and science in general.

Why is storytelling important?

Storytelling is the act of creating and sharing a narrative. Narratives help guide the audience through the work and provide a memorable framework. Compared to a spattering of data and figures, which causes confusion from hard-to-synthesize information, an effective narrative clearly communicates the big ideas and supporting evidence. Furthermore, it aids in keeping the audience focused by providing an interesting and understandable story. As the author or presenter,, you benefit from storytelling by receiving more thoughtful questions and useful feedback.

General structure of your narrative

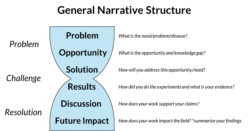

All effective scientific communication has largely the same general structure. This structure mirrors the common story arc of Problem, Challenge, and Resolution. Remember, your aim is to effectively characterize the problem, communicate your findings, and illuminate the impact. A useful exercise is to summarize your presentation in three sentences. This challenges you to focus your message and ensures your presentation matches your goals.

Below is a general narrative structure to follow:

From poster to thesis defense, this structure holds true for most communications. For multi-faceted projects with distinct stories, you may cycle through this structure a few times. A faculty talk or a thesis defense will likely have a few nested storylines within their overarching narrative. Each nested storyline communicates a ‘sub-problem’ within their larger ‘problem’. Next time you listen to a talk you really enjoy, keep an eye out for these storyline arcs.

Choosing your specific narrative

Now that you understand the general structure, identifying the type of project can help decide the type of narrative you will employ. In BE, projects commonly engage one of the following narratives: testing a hypothesis, improving/validating known outcomes, or developing a new methodology or system.

| Testing a hypothesis | Improving known outcomes | Developing a new methodology or system | |

| Theme |

Biology-centric |

Balanced

|

Engineering

|

| Research Focus |

Fundamental or Mechanistic |

Application or Translational |

Development or Optimization |

| Key Questions |

|

|

|

Although projects can fall in multiple categories, it is important to try and keep your communication focused. Let the status of your project, your audience, or chapter of your thesis be your guide. For example, at an early stage of a project choose to focus on method development, while later in a project you can focus on the applications of that method.

Adjusting your layout based on audience and format

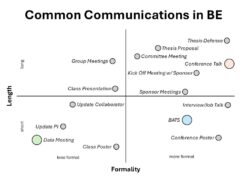

The main difference when applying these steps is in structuring them for particular audiences and goals/applications, such as soliciting feedback on experiments or providing a big picture overview. The plot below shows most of the communication needs we encounter in BE:

After deciding on a narrative of testing a hypothesis, improving/validating known outcomes, or developing a new methodology or system, the structure and ‘key questions’ will be tuned to match your specific communication goals.

A few main types of communications emerge from the above plot. Below is an example flow chart to tune your presentation from a formal, long conference talk to a formal, short BATS talk and a non-formal, short data meeting. Notice how the structure remains, while the level of detail and focus shifts as the purpose and length of the presentation changes.

In addition to considering the length and formality of the communication, the audience’s expectations and expertise are also paramount. For audiences that are not in your specific field (e.g. collaborators, sponsors, etc.), it is generally beneficial to invest in a longer and big-picture introduction with less focus on the technical or esoteric details of the project. Besides highlighting broader visions and objectives to appeal to a wider range of audience backgrounds, it can also be helpful to orient a more naïve audience by providing an overview of progress before diving into data showing new developments, significance, and next steps. On the other hand, when presenting to your research group, they may be already fairly familiar with the research problem and context. If you are seeking technical advice, increase the amount of detail when discussing your data.

Common hurdles in storytelling

When faced with the task of communicating our research as a trainee, we often have to deal with difficulties such as incomplete stories and choosing which data to present.

Incomplete or New Stories

At an early stage in developing a story, it is essential to hone your understanding of the context and purpose of your project and story. The context and purpose should be well explained and take up more of the presentation than in more complete narratives. Your audience is likely hearing about this project for the first time, thus the context and purpose need to be strongly emphasized and developed in order to solicit feedback on the goals.

Along these same lines, the methods, results, discussion, and future steps will look a little bit different than in more complete stories, but nonetheless can be compelling and exciting. These sections are an opportunity to present any preliminary data that you have gathered, which does not need to be perfect (see below for the second common hurdle). Preliminary results can still demonstrate what you have done or gained experience with, highlight ongoing avenues of exploration, and serve as a preview of future directions. Even if the results are not yet ready for publication, they may be solid enough to present, as long as you are open and clear with the limitations of the data.

Additionally, think about what challenges you faced and how you overcame them. Gaining experience and learning as a researcher during initial experiments is valuable and can be discussed, especially if the experience gained is directly relevant to the future steps of the project. As such, build in direct logical transitions from any initial experiments to the discussion and future steps sections.

The future steps component of an early-stages storyline should be strong and show the promising prospects of future explorations. The audience is interested in what you will do and the soundness of your plan for the future of the study. To help them evaluate this in the absence of actual data, it can be helpful to mock up the kinds of data you would expect from a given experiment and illustrate how you would interpret them. This makes the future steps more concrete and actionable for you and your audience.

In summary, when presenting an incomplete or new project, an effective storyline should emphasize the context and motivation of the project, highlight conflict/resolution pairs to demonstrate lessons learned, and finish strong with concrete future steps.

Choosing what data to present

The main part of any presentation is the claims which should connect together like stepping stones. Claims are not ground truth ‘fact’, but rather reasoned arguments that are supported with evidence and can be countered and debated. For an effective story, all claims need to be supported by evidence: this evidence can consist of positive data that you have already gathered or would like to gather in the future, or data that rules out alternative claims.

Counter-evidence is evidence that supports alternative claims contrary to the one you propose. These should not be hidden from your presentation, but rather should be addressed openly in the name of honest presentation of a complex picture. Additionally, evidence that does not clearly support a single claim is often inevitable in scientific research. When dealing with ambiguous evidence, it is good practice to acknowledge its shortcomings as proof for your chosen claim, and highlight it as an area where additional investigation will be needed.

Another natural outcome from going through this evaluation is realizing that your evidence does not support the claim you propose, but rather supports a different claim. This realization is a useful opportunity to revise your claim (and potentially larger argument) to better fit the available evidence. This new claim may be different in scope or focus—hopefully this new claim fits within your research goals, otherwise those goals may need to be adjusted as well.

Below is a simple decision tree of this process:

By following this process, you should be able to map out a landscape of both supporting and contradictory evidence, and likewise identify where your collected data fits (or likely does not fit) into your story. Looking at the overall narrative helps you identify what new evidence you might want to pursue to better support your claims, or alternatively you may realize the claims of your story need to be revised. These are natural parts of the storytelling-science feedback loop. As the research continues, the claims will evolve along with your understanding of the project.

Final stages: feedback and iteration

Effective communication is an iterative process of trial and error, writing and rewriting, drafting and revision. Seek out external perspectives and support: one of the most effective ways to evaluate whether your narrative is successful is to solicit feedback and use this additional perspective to refine your story. Trust the feedback, as these perspectives are likely more similar to your audience than you are. Set your expectations reasonably: it is usually hard to get an ideal story written on the first try, so grant yourself the permission for your first draft to be imperfect and try to build the time and mental space to revise and refine your story over multiple drafts. Remember the responsibility that you hold as the storyteller: be intentional and conscientious as you navigate the inevitable tradeoff between realistic detail and narrative simplicity, and exercise your best judgment to develop a story that is honest, clear, and compelling. These are key for a memorable communication. As a closing thought, attempt to write your story in only three sentences. Ensure all members of the audience are able to leave with that memorable story.

Blog post by Brandon Dorr and Jacqueline Gerritsen, Communication Fellows

Editing help from Jelle van der Hilst, Communication Fellow, and Han Xu, Communication Lab Manager

Posted Jan 2025