The Importance of Good Emails

Emails are the primary way professionals communicate with each other. Whether it be communicating with a professor, a collaborator, or a journal editor, your point of contact is often via email. The average person receives ~120 emails/day and spends about 11hrs/week sorting through emails (Plummer, 2019, Harvard Business Review). Writing a clear, concise email improves your chances of getting a response from your recipient.

The difference between a poorly written email and well-written email can be the difference between receiving a useful response or none at all.

Let’s look at two examples:

Email 1 on the left includes a lot of information and context, but the specific request, a meeting to discuss a rotation, doesn’t appear until the end. Professor Smith skims the email, misses the request, and fails to respond. Sarah has to send multiple follow-up emails to get Professor Smith’s attention and schedule a meeting. They meet in late October to set up a rotation in the Spring.

In contrast, Email 2 on the right frontloads the meeting request, providing additional context and scheduling information afterwards. Professor Smith immediately knows what this email is about and responds with a meeting time. They meet right away and schedule a Fall rotation.

Let’s break down these emails further and understand the structure and communication strategies employed to yield a positive outcome.

General structure of an email

Adopted from the Email for Action by Chelsey Angelone

The goal of an email is to communicate your purpose. Starting your email with the purpose ensures that your recipient knows why you are contacting them right away. Additional information can follow to explain or supplement your request. The exact email structure and what information is included depends on you, your audience, and communication goal. Regardless of what information is included, the most important aspect of an email is clarity. A long email that is well-structured and clear is more likely to yield a response than a short and unclear email.

Improving on an email: rotation request

Let’s revisit our example email and break it down.

This email has 3 main issues:

- Structure: the purpose of this email, requesting a meeting to discuss a rotation, is at the end of the email. People often skim or don’t finish entire emails, so putting the request in the middle or at the end of an email risks our recipient missing the purpose altogether.

- Information density: this email contains a lot of background information regarding their research background. While this information may be relevant to us, it isn’t essential for Professor Smith to understand and respond to our request. By putting it at the beginning of the email, it delays and buries our request. If this optional background information is included, it should be after our request.

- Formality and tone: when emailing a professional, err on the side of caution and refer to them formally. In this case, Professor Smith or Doctor Smith would be more appropriate. Additionally, maintaining a respectful and professional tone is essential in establishing communication with a new person. People want to feel important, respected, and valued.

Professor Smith may not read or easily understand this email, and we don’t get a response.

Taking into account this feedback, and a few tips & tricks, let’s write a new email draft that is more likely to get a response.

This updated email structures the email to be purpose-first, so Professor Smith immediately knows that we are interested in meeting to discuss a rotation. Additional context is provided below, but is optional depending on your email style. Intentional formatting, such as line breaks and bolding, increase readability and emphasize our request to schedule a meeting.

To efficiently schedule this meeting, we CC’ed Professor Smith’s administrative assistant and listed our general availability for the next month. Alternatively, consider using an online tool such as WhenToMeet or WhenIsGood to identify overlapping availability. These tools are particularly useful when scheduling availability between 3+ parties.

With this updated email, Professor Smith responds and we schedule a meeting in a timely manner.

Follow-up emails

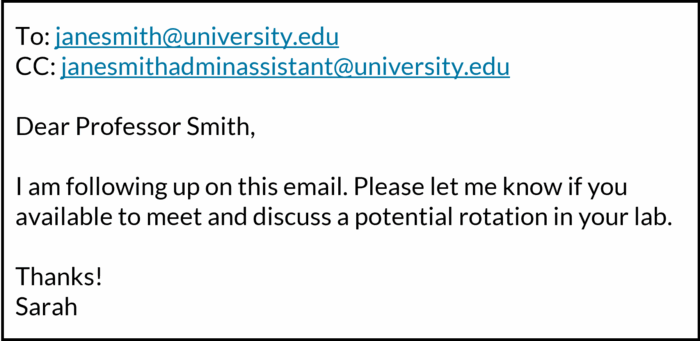

People are incredibly busy, so emails often don’t get a response. This could be due to the email being missed, forgotten, or your request being unclear. Depending on the importance and time-sensitivity of your email, you may want to send a follow-up email. This serves as a gentle reminder of your original email.

A follow-up email should be short and polite, reminding your recipient of your core request.

When determining whether to send a follow-up email, consider typical working hours. Professors may not read emails received outside of working hours (9-5 Monday-Friday), on weekends, or on holidays. Therefore, an email sent Friday night may not receive a response until the following Wednesday. For non-urgent emails, waiting 5-10 business days to send a follow-up is standard. For urgent emails, waiting 2-3 business days may be more appropriate.

Email tips and tricks

Subject lines – time sensitivity and/or specific requests

Often time emails are time-sensitive or have a simple but important request (e.g. signature on a document). Consider including this information in brackets [LIKE SO] followed by your subject line:

Confirmation of email receipt

Some emails may not have a specific request that requires a response; for example, sending a professor a document they requested. However, to verify your recipient has seen your message, you can request a confirmation of receipt in your email: “Please confirm when you have received this document.”

Email attachments

When attaching a document, consider the optimal format. Many document types store information such as editing history, which you may not want your recipient to have access to. If a document does not need to be editable, send it as a PDF. If the document needs to be editable, or is hard to read as a PDF (e.g., PowerPoint with many animations), then send the document in a Word, PPT, etc. document format.

Text formatting

Using bolding, underlines, and/or italics can be useful to emphasize key information within your email. However, they should be used sparingly – if everything is bolded, nothing will be emphasized. Avoid other formatting such as different fonts, text colors, etc..

Other text formatting options, such as indents, bullet points, and line breaks can also be used to create a more readable email. Numbered bullet points are particularly useful for emails which contain multiple requests. This allows your reader to keep track of each individual request and provides them a template to respond with:

Adopted from BE Comm Lab Professional Email toolkit by Sarah Schwartz and Sarah Bening

Addressing your recipient

When you are not sure how the recipient likes to be addressed, always err on the side of too formal. Here are some titles you may encounter, in decreasing order of formality:

- Dean/President/Provost

- Professor (Prof.)

- Doctor (Dr.) – used to refer to any individual with a PhD or equivalent doctorate degree (e.g., postdoctoral researcher, lecturer, etc.)

- Mr./Ms. (avoid Mrs. Or Miss)

These titles are followed by the individual’s last name (e.g., Dean Smith, Doctor Chen). After they reply, you can usually go by their email signature. If you have an established relationship with the recipient, refer to them as you normally would in conversation.

In situations where you don’t know who the recipient is, make the best guess of their title and err on the side of formal.

- Emailing for job applications – “Dear hiring manager” (if the posting does not contain a contact name)

- Emailing fellowship organization – “Dear reviewing committee of XY fellowship”

- General unknown recipient – “To whom it may concern”

The formality of your email writing should also match your audience. A cold email to a Professor should be formal, while an email to a professor you know well may be more casual and short.

Email timing etiquette

Many people only read and respond to emails during normal working hours, 9AM-5PM Monday through Friday. Unless you have an established relationship and know they will read your email outside of those hours, it is most respectful to send emails during that time period. Non-urgent emails generally should not be sent outside of normal working hours, regardless of your relationship to the recipient. When working with people in other time zones, try to send emails during the working hours of their time zone.

Scheduling emails is a useful way to write emails at any hour but send them at a designated time. Various email applications (Gmail, Outlook, etc.) offer schedule-send options that can be utilized to send an email at a predetermined time.

Blog post by Sarah Nemsick, Communication Fellow

Various content adopted from Professional Email CommKit article by Sarah Schwartz and Sarah Bening, Communication Fellows

Editing help from Han Xu, Communication Lab Manager

Published Oct 2025