…

Sooo…

What are you avoiding right now?

Come on. There’s no way you’re reading this unless you’re avoiding something. You’ve got an Overleaf document open. You’ve copy and pasted the abstract that was accepted into the conference you applied to months ago. You’ve got your literature review spreadsheet, your results, and code open. You’ve locked in on your favorite song, “8 Hours Super Deep Brown Noise Sleep, Study, Focus NO ADS.”

And you’re in another tab. Any other tab.

If you’re anything like me, actually getting started writing is harder than any other part of the writing process. For most writing assignments in undergrad and through my masters, I would consistently find myself waffling through writing something, unable to focus and make significant progress. Suddenly, when the due date was upon me, I’d finally find my focus, as the time pressure gave me no choice. One miserable all-nighter later? Paper done. Never punished.

Maybe this was sustainable when I was an undergrad, but I’m old now. My body can’t run off of stale brownies pilfered from free food events and tea flavored by the crusty remnants of previous cups anymore.

I have bad news: those habits are a large reason why focusing on starting writing is hard now. My brain has been wired to associate writing with painful crunches. Trying to start writing tells my brain it’s time to go into crisis mode, and the stress puts me off of it entirely.

I had to find another way, and you can too.

Here are 7 tips I’ve found that are helpful for coping with getting started. Not all of these may work for you, since everyone is different, but you won’t know until you try.

1. Understand why you can’t focus

The first step to solving a problem is admitting you have a problem. We treat focus as something you choose not to do, but that isn’t the case at all. If your solution to being unable to focus is to yell “FOCUS” at yourself, you just stress yourself out, which makes you want to relax, which puts you on Instagram, which makes you mad for “wasting time,” ad infinitum. Your limited focus is a resource that you drain the more you allow yourself to multitask.

Set yourself up for success by structuring your time. If you have a set amount of time for working on something before you can take a break, it is easier to avoid doing your “break” things while working. I have a little extension on my browser, as well as this website, that I can click to start a 25 minute timer. During this time, I only work on a single task and mute everything else. Once it’s over, I take a short break. I emphasize this to myself by listening to different kinds of music in work and break blocks. Building this habit helps disincentivize mind wandering.

You can take this a step further by structuring your entire day. Break up projects and tasks and mark which hours you’re going to work on each in your calendar. Extend this beyond work too – from 8-9 PM tonight, you’re reading a book!

When you do find your focus drifting during a work block, don’t get mad at yourself, but also don’t indulge it. You don’t do things for no reason: whatever you’re getting distracted by matters. Are you distracted by another piece of work? Makes sense: has to get done too. Are you distracted by a recommended YouTube video? Also makes sense: you like them. Don’t punish yourself for liking things! Write down what you got distracted by, why (and yes, your why can just be “I like Pikachu”), and then go through the list during your next break.

If you are interested in finding out more, in much more detail, I recommend this YouTube video. It’s witty, well researched, and thorough, and discusses this better than I ever could.

2. Put everything you have in one place

Now that we’re actually in a work block, what do we do? Don’t just jump right into writing a piece on page 1 – that will land you in the frustration-distraction-anger-nothing done loop. Instead, let’s do a productive thing that isn’t the productive thing you’re “supposed” to be doing.

Take out a blank document or a notebook and start noting what resources you have, where they’re located, and a brief summary of what they are. These can be anything relevant to your task. Sure, you have your results and your literature review, but you also might have a slide deck on this topic you made for a lab presentation, or a statement of work from proposing the project. Assess what in them is useful and, more importantly, what is missing. Finding these gaps can be very helpful to give you direction on where to work from.

Once you have all of your resources, put them into buckets. Which pieces are useful for which topics? You have some snippets of work that go into your methods. You have some data that you have half a plotting code written for that would go in this section.

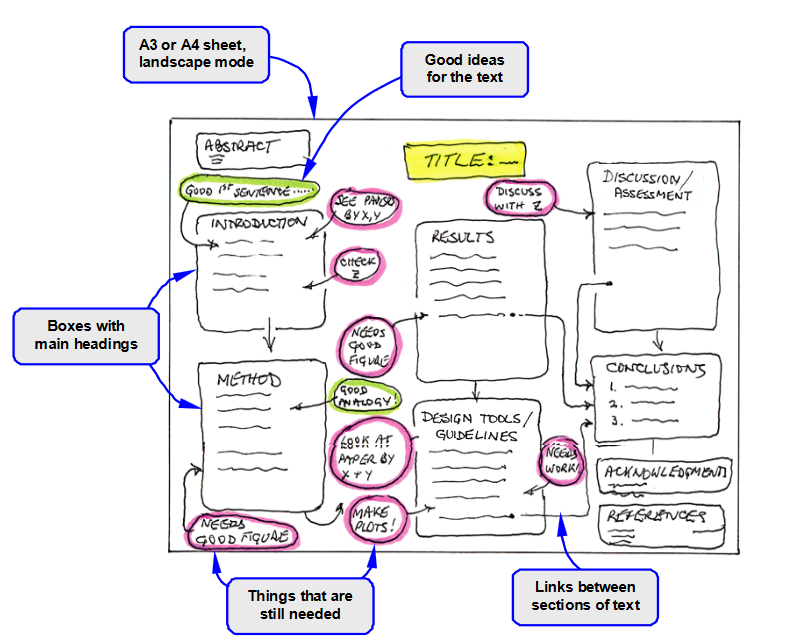

You can structure these into a flowchart if you’re feeling really ambitious. Again, nothing too fancy. Mark how your ideas lead logically into each other and make notes on what’s missing.

This is a model for an organizational flowchart from “How to Write a Paper” by Mike Ashby, another fantastic resource about the more technical aspects of paper writing. Ashby organizes the ideas and needs for the paper into different areas. All rights reserved by author.

Okay great. Guess what you just made?

An outline.

That’s right. I tricked you into making your outline.

Plenty of people find the act of “making an outline” useless, but, more often than not, it’s because they were never taught how to properly make one. If all you think an outline is is INTRO METHODS RESULTS DISCUSSION CONCLUSION bulleted list, yeah, that doesn’t give you any direction. By instead connecting your actual content to it, you make less of a map for your paper and more of a guided tour. This not only gives you important to-dos (concrete tasks beyond “write a paper!” huzzah!), but also gives you assurance that you have already done work.

3. Chunk your tasks

Telling yourself that today you’ll work on your paper is nebulous and scary, but what about telling yourself that today you’re working on three paragraphs of your literature review?

As we have stated already with our foray into focus, the biggest hurdle to getting something done is multitasking. When you’re facing “writing a paper,” there are dozens of substeps you need to handle in order to get it done. If you end up spending 3 minutes on writing a lit review but then 2 minutes looking at requirements for the paper but then oh wait you need to spend another minute on rereading this one paper and – and – and –

Well, you’re left with a bunch of disorganized notes all over the place. Odds are, you’ll forget exactly what was done during this time and may need to do it all again. Be more disciplined and organized about this. If you’re working on your literature review, that is all you’re working on.

The bonus to this tip is it works fantastic with tips 1 and 2. Tip 2 (sneaky outlining) gives you specific TODO tasks that can really easily be chunked into these microtasks. Tip 1 (focus time) suggests making specific blocks of time for yourself to do things. You can assign those chunks to 25 minute long work periods! Now you know precisely what you’re working on, when you’re working on it, and how long you will be working on it.

4. Write it terribly

Have you ever noticed that it’s a lot easier to criticize things than it is to make things? You can probably give me a hundred reasons why The Rise of Skywalker was a bad movie, picking out specific scenes and plot points you would change if you could. But if I shoved you in a time machine, sent you back to 2018, and assigned you to write the ninth Star Wars movie from scratch, you’d almost certainly fail, possibly just as spectacularly. Starting fresh is much harder than starting off a baseline.

You can make your own baseline: instead of writing something good, write your paper as bad as humanly possible to start.

I was struggling on an introduction once and wrote this instead:

Satellite data collection – what can’t it do? It has blessed us mortals with the ability to spy on our marble from the heavens as if we were gods. Even blurry, smudged pictures taken from cameras strapped to pizza boxes delight and amaze. The curve of the Earth is more beautiful than… no, I shan’t say it.

This isn’t a usable piece of text, but you can break it apart to find what is usable in it. The ideas are in there: all you need to do is doctor them into something useful.

You can also turn this method down somewhat. Instead of writing poorly on purpose, word vomit. Rip the backspace key off of your keyboard and get typing. Do not let yourself edit as you go: just get it all down. Even if you have mistakes, keep going. Even write “oops nope not that.” Get it all out of your system and don’t care one bit about quality.

There are two main reasons that these methods are useful. First, as I said, ripping apart and editing things you know are bad is easier than generating new things. A blank page is terrifying, but a page full of words is progress. The other reason these methods work? You actually wrote something. You have now turned your brain into “writing mode” instead of “not wanting to write” mode. If you’re familiar with brainstorming techniques, you may have done something similar. In effective brainstorming sessions, you always take “no bad ideas” seriously to a fault. You write everything anyone comes up with down, even if they are clearly just joking. The idea is to get everyone into a mindset where they’re firing their brain up to think of things, which can then spark “real” good ideas. Writing is just the same way!

5. Don’t start at the beginning

Introductions to papers get progressively more boring the longer you’ve been in a field. If I have to read about how CubeSats have revolutionized space one more time, I might eat my computer. They are necessary: they ground what you are writing for unfamiliar readers and clear up common assumptions for experienced readers. This doesn’t make it any easier for you to write it when you’ve read the same type of intro over and over.

Start anywhere else. I usually start with the literature review, since it requires me to think about the topic without having to think about my own work, where I can get caught up on little details. Maybe it’s easier for you to start by summarizing an experiment or a result you have. This can help break up the writer’s block and get you writing.

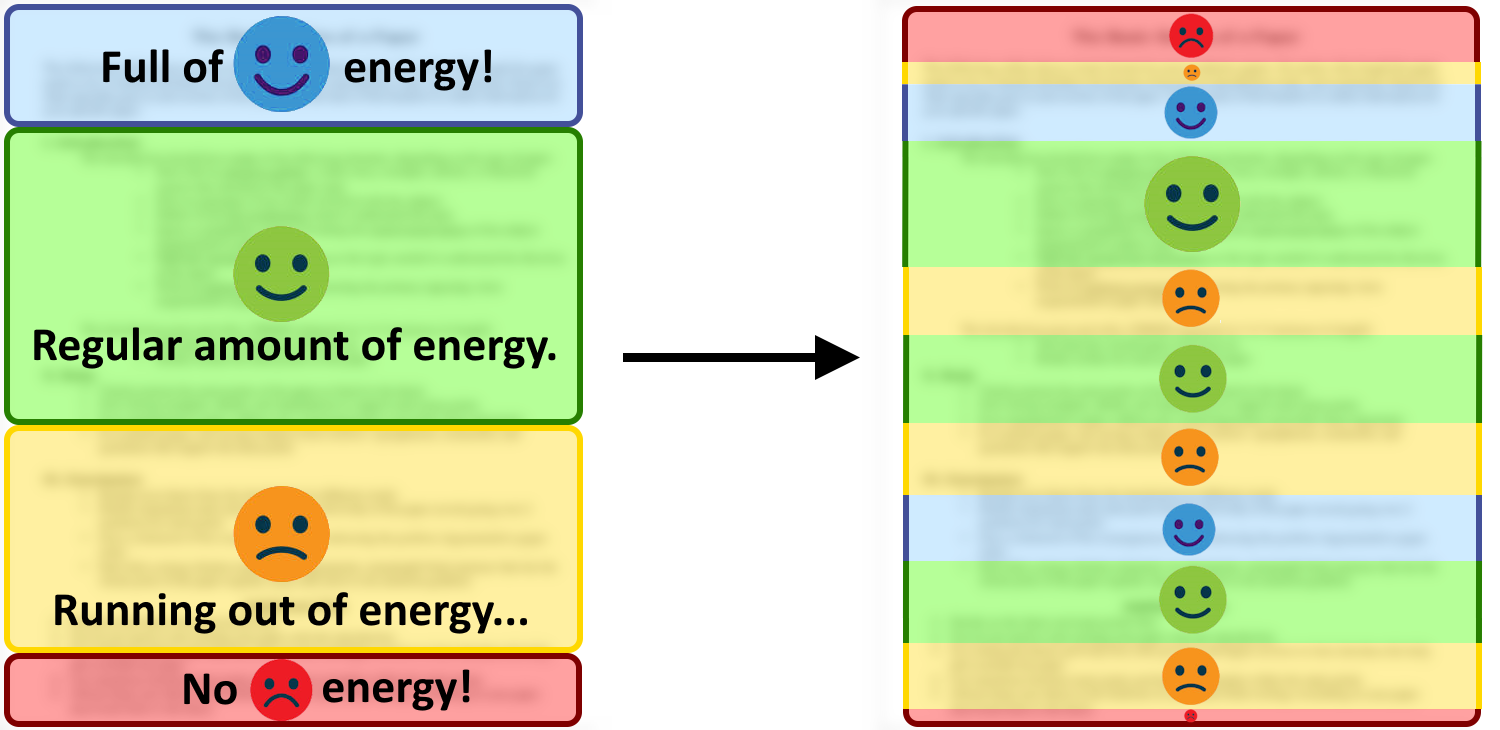

Another reason that you shouldn’t start at the beginning is to distribute your energy. Be honest with yourself about past papers you have written: have you ever allocated the right amount of time to writing them? You probably spend far too long writing and rewriting the beginning, while you feel like you have plenty of time to get the paper out. As you run out of steam as the due date approaches, your writing quality suffers. Shuffle up the order you write things so you can ensure that you keep some of that early-writing energy for every section of the paper.

Typically, when we write a paper in order, our energy level decreases as we write. Because of this, the quality of our writing peaks at the beginning, which is relatively less important to the paper, and declines as we go. By mixing up the order we write the paper, we can ensure that some of that high energy is dispersed.

6. Move your internal due date up

Oh, that paper is due in a month? Cool, cool, cool.

Nah, it’s due in 2.5 weeks now.

Wow, this sucks! Now you need to be a lot more efficient about getting it done. Now you need to pressure yourself into focusing. The way that you would… do… if… it was last minute… the only time you could write…

…

Haha, tricked your brain again.

This one can be difficult to actually get done, since you are fully aware you’re trying to trick yourself. (I know that Mary is a liar and that I can in fact have that brownie whenever I want it, thank you very much.) The exact amount of time you trim for your due date is difficult to figure out, but I’d recommend trying to get it done in ⅔ of the time you actually have.

With that extra time, you can actually do substantive edits. Give the whole thing a thorough read through and have better ideas about what needs punching up. It’s even better if you can get your advisor extra time to read it. If you’re really lucky, you might even manage to be able to use that extra time to relax. I mean, probably not, but it would be great!

7. Talk about your paper with someone in a new location

If you are really struggling to get things started or to keep your synthetic due dates, turn to your officemate, your best friend, your milkman, your pet rock, anyone, and ask them if you can grab a coffee and summarize your paper for them. This is the same idea as we’ve been saying: you’re so caught in your own head about the topic that you can’t figure out how to get the words out. You’ve been working on this for so long that you’ve forgotten that you enjoy the topic.

But look at me: you are talking about the paper.

I know, breaks are supposed to be for resetting your brain, but all talking about other things does is make you not want to go back to work. Sorry I have to be a bummer here, but I’m here to try and help you to write your paper. Go to a new location and set an end date for your chat. Just talk about it. The ins and outs, what you’re stuck on. Treat your friend as a sounding board until you’re thinking again. Set your synthetic due dates during this meeting, and check back in with them to show progress.

Man, if only there was a convenient location on MIT campus where you could talk with a colleague about your paper. If only there was some resource where your colleagues have been trained to discuss technical writing at length. If only you could sign up for a half hour or hour long block to discuss your paper, no matter what stage you’re at. Hmmm… oh wait, you could always go to the MIT AeroAstro Communication Lab!

That comes to the end of our list. Hopefully, some combination of these strategies will be helpful to you. In short, remember these two things:

- Make specific time to do specific things.

- Force yourself to get something out, written or out loud.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have a thesis proposal to get started on.