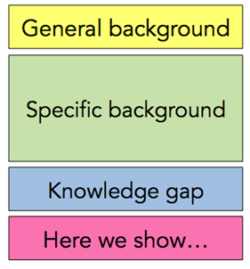

Criteria for Success

- Establish the overall scientific settings of your research. (“General Background”)

- Introduce the minimum essential information your audience needs to understand and appreciate your work. (“Specific Background”)

- Illustrate the incompleteness of the current understanding and the value of investigating the field further. (“Knowledge Gap”)

- Give a brief preview of your findings and how they relate to the central question or problem. (“Here we show”)

Structure diagram

This structure is like the first half of an Abstract.

Identify your purpose

Your paper’s Introduction should provide your readers with the all information they need to grasp, appreciate, and build on the knowledge you present. Having read the Introduction, the reader should feel well-equipped and eager to understand your study and its significance.

Analyze your audience

Scientists in your specific field will probably understand your work’s motivation whether they read your introduction or not. They might even skip the Introduction and focus on the Methods and Results. Outsiders are the people who will benefit most from a well-crafted Introduction. This means:

- scientists outside your research area

- public or policy officials, educators, or industry professionals who could benefit from your research

- editors assessing whether your work might be a good fit for their journal

Focusing on outside readers will affect two parts of the Introduction:

- It will increase the General Background’s breadth. Imagine you are developing a black, absorbing material for collecting solar thermal energy. For an insider audience, you might write a paper that begins with a summary of known coatings and strategies for solar thermal harvesting. For an outsider audience at a broad-readership journal, the General Background—the thing everybody cares about—will broaden from solar collection design to its global impact in renewable energy. You might instead start off with information about the advantages of solar thermal energy in the current energy climate.

- It will lead to a less technical Knowledge Gap. The more basic the question posed in the Knowledge Gap, the more people will care about it. Take the time to identify the simplest, most fundamental question your work answers. More technical questions will attract smaller, more specialized readership. If you make your results seem less general than they actually are, you immediately limit your audience.

Breadth, length, and comprehensiveness of the Introduction are highly dependent on the journal you submit to. Analyze papers from your target journal and follow the journal’s guidelines.

Skills

Orient outside readers

Start off with something everybody relates to and/or cares about. Then, give your reader a sense of past accomplishments, current contradictions, and competing theories in the field. Cite previous work that illustrates your narrative and gives a balanced description of the landscape of research in the field. Give credit to others for their contribution to your scientific topic.

Give your readers the technical details they need (and nothing more)

Once you have brought to the overall value of your work to the audience’s attention, you must give them all the tools needed to understand the details of your approach and of your results.

Point out how your approach and/or method stands out compared to previous approaches, and how they are capable of addressing the questions left unanswered by previous work.

Declare all key terms and all acronyms. They should be the main characters in your paper from the outset.

Remove anything that is not related to the Results or Discussion. By including unnecessary knowledge, you run the risk of overpromising, making a reader expect to hear more about a topic and then leaving them hanging.

Your purpose is not to showcase the breadth of your knowledge, but instead to give readers all the tools they need to understand your results and their significance.

Define a narrative

It’s often helpful to write your Introduction after you develop the Results and Discussion sections. The story you choose for the Results and Discussion sections will determine which theories and past research or methodologies need to be presented in the Introduction.

Connect the “Here we show” part of your Introduction with the Results and Discussion rather than Methods. Use the strongest claim(s) and conjecture(s) from the Results and Discussion (respectively) to foreshadow your contribution in “Here we show”.