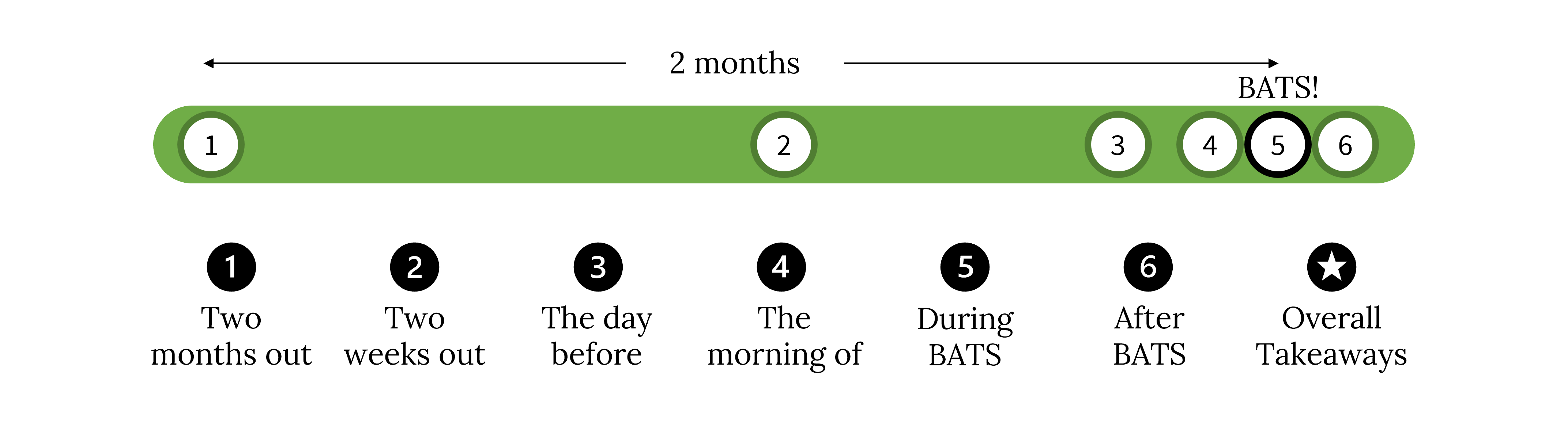

This blog post will follow a roadmap format—jump in at any point no matter how much time you have until your own BATS:

At face value, BATS might seem like one of the most intimidating aspects of the entire Biological Engineering PhD. You may feel like it is too early to share your research progress with the department—it may be the first time you’ve spoken in front of a large audience of peers and professors—and perhaps you feel worried about being compared to the other speakers. These are all natural fears we, the authors, felt when BATS snuck up on us faster than expected, but we ended up having a great time working together throughout the whole process. We aimed to write this blog post to:

- demystify the BATS process from start to finish

- sketch out a useful working timeline that worked for us

- encourage you to enjoy the process and results of giving BATS!

In addition to the BE Department graduate students, this post should be broadly helpful for any new scientists planning for a successful short talk. There are also many excellent resources available through the Communication Lab, including a rubric for the Wishnok Prize, speaker suggestions for the Wishnok Prize, general BATS guidelines, more specific tips for success, and through the BE Department Student Handbook. Finally, we recommend making appointments with either of us or anyone in the Communication Lab to discuss your own talks!

What is BATS? How is BATS planned?

The Biology And Toxicology Seminar (BATS) is a weekly seminar featuring two BE graduate students per session; each talk is approximately 15-20 minutes, followed by a question session and feedback collection. Each student will give one BATS talk in their third year fall and one in their fourth year spring. BATS scheduling takes a different form every semester, guided by the wishes of the presenting cohort, but in general there will be a survey of preferred dates and unavailable dates. It is recommended to consult with your PI and your labmate(s) in order to coordinate date selection; many students try to present with their cohort/labmate on a date the PI is available.

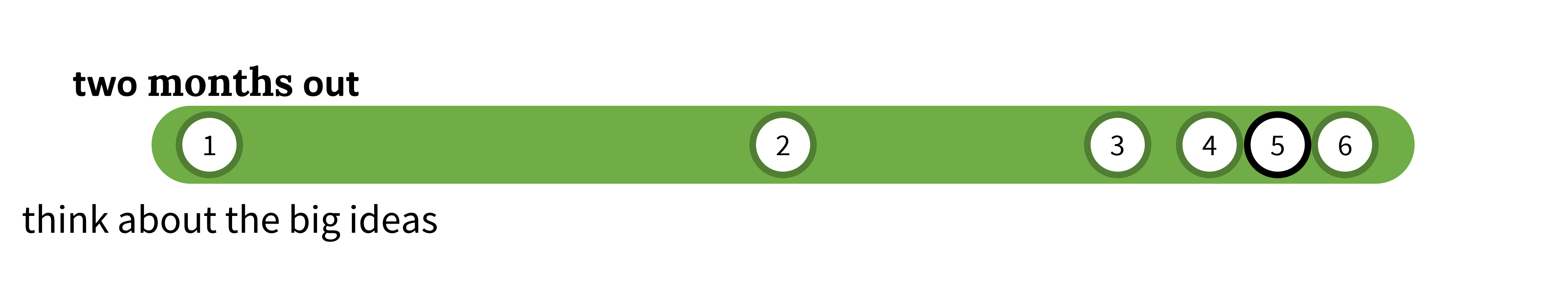

With several months left to go before BATS, this is a great time to start thinking about the general story and flow of your project. If you have multiple projects, you could think about which would make the most useful and compelling story; perhaps one project is wrapped up and finished, but you’d like to share and get feedback on a relatively new project, or you’d like to highlight great work that ended up as a publication already. If you feel like you don’t have much to present, don’t worry! Many people present without much data, and some projects just move faster than others. The main thing is telling a good story by motivating your project goals, placing the work into the literature context, and showing how whatever data you do have informs where you’re going with the work.

Once you have sketched out a broad idea for your talk, you could consider whether there are any experiments you’d like to perform before the presentation. Perhaps you’re working with a lineup of proteins and you’d like to repeat your first few messy Western Blots to make them clean and presentable for a figure, or you’ve been putting off doing replicates of some early confusing data but you’d like to strengthen the figure with error bars. This is the time to refine your figures so they are simple, intuitive, and polished.

If you aren’t already going to BATS, this would be a great time to resume attendance for several reasons: you can support your cohort, learn about the cool science they are doing, and soak up science communication tips and tricks all at the same time. What can you learn in terms of communication from each speaker? Are there particular figure styles or formats that you think are really great?

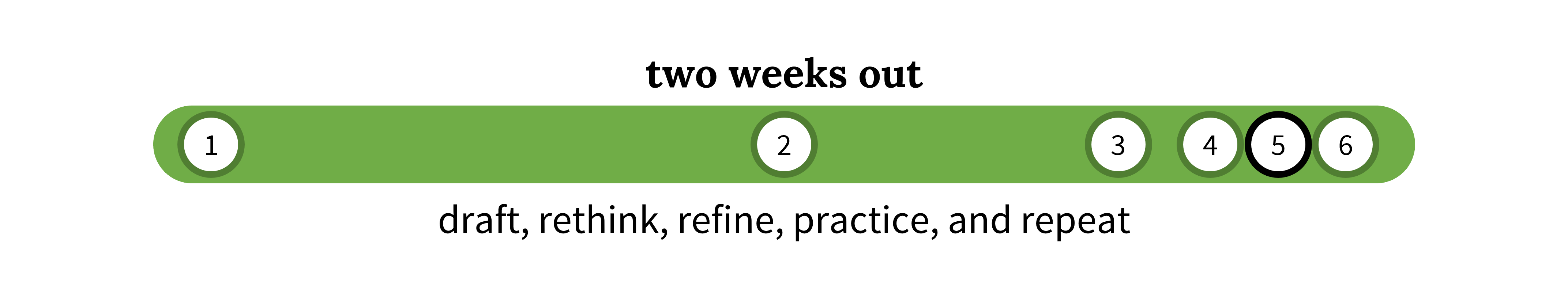

Ok, BATS is getting closer. A few weeks to a week before is when you should be putting in the bulk of the work for drafting and finishing your slides. Your third and fourth years are a great time to start building a cohesive “mega” slide deck—all your group meetings, committee meetings, proposal, and BATS slides will draw from the same figures and data, and a figure made for one of the above will probably work for all of them. Time spent making a great figure now (and mastering matplotlib/Illustrator/your data analysis tools of choice) is time extremely well spent for the rest of your PhD.

For this talk in particular, let’s take a moment to think about the format and audience, and how they will inform your slide development.

Format: BATS is a 15-20 minute presentation, which is relatively fast-paced. You’ll be spending very little time on even your most complex figures, so you’ll want to make sure figures are quick, easily digestible, and have a high signal to noise ratio (they make your message very clear and do not have distracting, ‘noisy’ elements like excessive tick marks, labels, graphic effects, etc.) It can be tempting to cram as much information as you can onto a figure slide to make sure the audience will really understand it, but in practice it is likely they will be overwhelmed and try to read/look at every element on the slide at the cost of listening to your words. We recommend effective redundancy: your spoken words should be similar (redundant) to the title and content of the slide, so the audience is not forced to choose between listening and reading (they will attempt both and be distracted either way!)

Audience: The BE department professors and graduate students span a range of very different fields. A computational biologist may not be familiar with a molecular biology/cloning workflow, and a synthetic biologist might struggle to follow really dense, field-specific immunology acronyms. Try to explain very clearly any field-specific jargon or diagrams early on in your talk and keep jargon/information overload to a minimum for a general audience.

When you have a rough draft ready, the fun work begins: editing and polishing! If you haven’t already, this is a great time to reach out to your colleagues, PI(s), and the Comm Lab for feedback and advice. Colleagues and PIs, especially those outside your direct subfield, can be useful in helping you identify and remove jargon. Ask if your lab would be willing to listen to a practice talk when you have a draft ready, and mention you are interested in feedback before starting so people will take notes and stimulate a feedback discussion afterward. Check with your PI(s), who might like to see and give feedback on your slides—communicate with them early to make sure you’re on top of their expected internal draft timelines! Finally, the Comm Lab is a great resource for your BATS slides. Appointments can take any form, from brainstorming your storyline very early on to a practice talk the day before; maybe you only want to work on one difficult figure, or you’re worried your flow isn’t quite right. Not only have many of us been through the BATS process, but we love to work with you on improving the general flow and communication of this and all your future talks!

As we found out, the best resource for your presentation can be your BATS co-presenter! We took a lot of time in the week before to present to our lab back-to-back, book empty conference rooms and classrooms, bounce drafts and figure improvements back and forth, and practice practice practice. It was really fun to watch both of our talks evolve and improve significantly over the process of our collaboration, and, more importantly, the talks were much stronger and easier to follow. We both noticed that it can be easy to get too attached to specific figures and slides, and it can take another perspective to step back and fix content that might be confusing for everyone but you.

A note on helping other people with their talks: trust your gut—if something wasn’t clear or you find an axis difficult to follow or even you just don’t like the flow, don’t feel like it’s just you being dumb. You won’t be the only one struggling with these concerns, and it’s best to share them now instead of letting the presentation suffer in front of the department. Additionally, best constructive feedback can include ideas on how to address the issue. Finally, noticing and encouraging the elements of the presentation that were fantastic is important! Build their confidence and make sure they know what is awesome about their presentation.

A note on taking feedback from others on your talk: Listen diligently to feedback. If something was confusing, explaining it to the single person giving feedback will not make the slide more clear when you present it at BATS. Stand by your data, while acknowledging its weaknesses. No data is perfect but should communicate your claim.

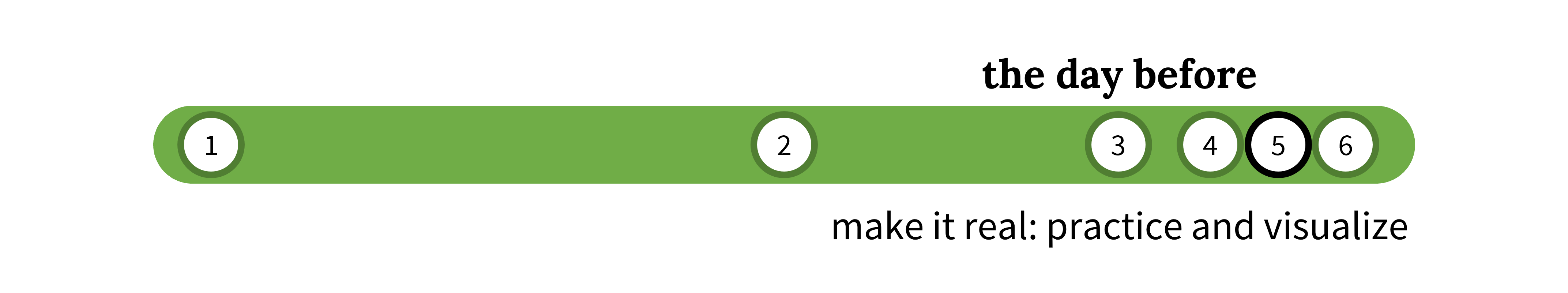

Practice as closely to the actual BATS format as you can. Stand up, speak loudly, get a lab conference room or classroom with projector, try to speak slowly, and time a real run through. Check your slides on a projector—are they faded or are the colors badly rendered? Is the text too small to be seen across even a small room?

It may be too late to solicit significant content feedback, but practice in front of cohort peers, friends, roommates, and/or family just to get a feeling for talking in front of an audience. Encourage questions during or after your presentation for two reasons:

- If things are unclear to this non-field-specific audience, this is your last chance to expand slides or make a mental note to explain a concept or term more explicitly in the actual presentation.

- Any scientific questions can give a hint toward the questions you may be asked after your actual presentation, so make sure you are comfortable answering them.

Visualize! Visualize the host calling your name and reading your title, then you walk up and look out at the crowd! See everyone looking back at you, say thank you, and introduce your talk. Visualize some faces intensely looking back at you and listening to every word, and some faces with drooping eyelids from a post-pizza crash. Feel your voice projecting to the audience in the back and feel your smile as you thank everyone for being there. It may be silly, but “mental rehearsal” can help you win gold medals.

Finally, get a good night’s sleep! Unplug from your presentation.

Have a relaxing morning–dress nicely in smart to business casual, like what you would wear to an East Coast conference, and have a solid breakfast for energy, maybe hold on the foods that may make you sleepy. Get to the room early, or head to BE-IT for a last-minute slide check before your talk. Once in the room, check the acoustics (have your speaking partner stand in the back and practice your speaking voice—is it too soft?) and do a final run-through of your slides on the projector there to make sure they all render appropriately. BE-IT will be on hand to help with any necessary Zoom setup, microphone and pointer activation, and recording.

Deep breaths and once again, visualize the moments you are most worried about. See them go off without a hitch and everything being a total success.

You’ve made it to the big moment! Remember to relax and treat this as a fun, enriching experience you have the privilege and opportunity to do; the audience will be genuinely supportive and curious about your work, so speak directly to them and share your passion. In terms of technical tips, make sure to speak loudly and slowly; modulate your speed and tone to emphasize important points and leave pauses after big take-aways; and do not be afraid to show humor and personality.

You have practiced and you know your presentation inside and out. Focus on the delivery, your nerves, and any portions which still might hang you up. While it is important to present without a physical script, you may have memorized a specific mental script or it might be more fluid and improvised off your talking points and slide content; whichever you do, do not get flustered if you forget to say something or veer slightly off-script. The audience does not know what you had intended to say, and won’t miss anything you forget to mention!

After your acknowledgements, it is good practice to end with a summary slide showing your key messages and experimental summaries. This reminds the audience of your work (as soon as I see an acknowledgments slide I forget the last 15 minutes of scientific content) and refreshes any questions that may have come up during the talk.

When answering questions, make sure to repeat them to the virtual audience (they cannot hear questions far from the speaker’s microphone). Make sure to also take time to answer questions, and answer honestly. The audience will not ask “gotcha” questions or try to trick your or expose flaws, so treat all questions as genuine curiosity and respond in kind. You do not need to know all the answers of the universe. Feel free to state that you do not know, but you then can conjecture. Labeling conjecture as such enhances your credibility. We find it can help to give experimental and literature context in your answer:

Experimental: If someone asks about your experiments and whether you tried XYZ conditions/techniques/tricks, feel free to talk about what you tried, didn’t try, and data you haven’t shown (maybe you could have a few extra figures of appendix data to anticipate these questions). Thank them for their suggestions if appropriate!

-

- [When given a solvent suggestion] “We did actually try DCM and hexanol as solvents, but in our hands the results were inconclusive so we proceeded with the toluene I showed. I’ll go back and try them at 12°C – thank you for your suggestion!”

- [For computational work] “We haven’t had a chance to experimentally validate these results yet, but we absolutely plan to in collaboration with XYZ groups.”

- [When asked about controls/other data] *flipping to appendix slides showing data from old experiments* “We did perform controls using XYZ mouse lines, but all lines showed the same behavior absent our treatment regimen, so I only showed one control for brevity. Here are all the control graphs.”

Literature: If you happen to be familiar with recent papers or work, or can anticipate questions from groups in the audience working on similar projects, feel free to share!

-

- [Are you familiar with so and so’s work] “We haven’t actually tried that protocol in lab yet, but as soon as we solve the purification bottlenecks I’m excited to implement that paper.”

- [This and that recent paper suggests an alternative hypothesis for your results] “I’m familiar with that work that came out recently, and it will be interesting to see if our results confirm or conflict with theirs; it’s worth nothing we are looking at XYZ condition they haven’t tested, so that might explain the different results.”

Be honest about flaws and drawbacks if asked—this will show you’ve thought about where the project is going, and also helps you get the most useful feedback. Most of our feedback was suggestions in response to experimental issues we’d mentioned in our talks.

Congratulations, you’re done! Take a bit of time to relax and recover from the presentation stress. Try to note down all suggestions, feedback, and interesting questions while your memory is fresh; send follow-up emails if needed if people suggested techniques or improvements and you’d like more information. You can also make a Comm Lab appointment to discuss your presentation, the feedback, or any other skills you’d like to work on.

Don’t worry about your data or lack thereof—focus on telling a good story with the work and learning you’ve done so far and don’t compare yourself to other speakers. Projects move at very different paces and people join at very different points. If you have negative or very little data, that’s ok! Just share the story and ideation of the project, some literature background or previous work that gives you hope the current project will work, and what your data or next results might look like.

If it is your second BATS, don’t assume the audience will remember anything from your previous BATS—pretend this is an entirely standalone presentation to a new audience. Your introduction and background motivation should still be accessible to someone who is completely unfamiliar with your work.

It’s natural to be nervous, but try to also have fun with the process. It is a great chance to work closely with your lab colleagues, learn some new communication tricks and improve your communication style, and this is one of the only times you’ll have a room full of students and faculty giving you their full, undivided attention and interest in your project. You could get some really cool perspectives and suggestions!

Blog post by Jelle van der Hilst and Brandon Dorr