| Table of Contents |

Introduction

The goal of this article is to help you to streamline your writing process and help convey your ideas in a concise, coherent, and clear way. The purpose of your proposal is to introduce, motivate, and justify the need for your research contributions. You want to communicate to your audience what your research will do (vision), why it is needed (motivation), how you will do it (feasibility).

Before you start writing your proposal

A thesis proposal is different than most documents you have written. In a journal article, your narrative can be post-constructed based on your final data, whereas in a thesis proposal, you are envisioning a scientific story and anticipating your impact and results. Because of this, it requires a different approach to unravel your narration. Before you begin your actual writing process, it is a good idea to have (a) a perspective of the background and significance of your research, (b) a set of aims that you want to explore, and (c) a plan to approach your aims. However, the formation of your thesis proposal is often a nonlinear process. Going back and forth to revise your ideas and plans is not uncommon. In fact, this is a segue to approaching your very own thesis proposal, although a lot of time it feels quite the opposite.

Refer to “Where do I begin” article when in doubt. If you have a vague or little idea of the purpose and motivation of your work, one way is to remind yourself the aspects of the project that got you excited initially. You could refer to the “Where do I begin?” article to explore other ways of identifying the significance of your project.

Begin with an outline. It might be daunting to think about finishing a complete and coherent thesis proposal. Alternatively, if you choose to start with an outline first, you are going to have a stronger strategic perspective of the structure and content of your thesis proposal. An outline can serve as the skeleton of your proposal, where you can express the vision of your work, goals that you set for yourself to accomplish your thesis, your current status, and your future plan to explore the rest. If you don’t like the idea of an outline, you could remind yourself what strategy worked best for you in the past and adapt it to fit your needs.

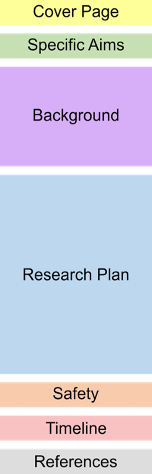

Structure Diagram

Structure your thesis proposal

While some variation is acceptable, don’t stray too far from the following structure (supported by the Graduate Student Handbook). See also the Structure Diagram above.

- Cover Page. The cover page contains any relevant contact information for the committee and your project title. Try to make it look clean and professional.

- Specific Aims. The specific aims are the overview of the problem(s) that you plan to solve. Consider this as your one-minute elevator pitch on your vision for your research. It should succinctly (< 1 page) state your vision (the What), emphasize the purpose of your work (the Why), and provide a high-level summary of your research plans (the How).

- Background.

- You don’t need to review everything! The point of the background is not to educate your audience, but rather to provide them with the tools needed to understand your proposal. A common pitfall is to explain all the research that you did to understand your topic and to demonstrate that you really know your information. Instead, provide enough evidence to show that you have done your reading. Cut out extraneous information. Be succinct.

- Start by motivating your project. Your background begins by addressing the motivation for your project. If you are having a hard time brainstorming the beginning of your background, try to organize your thoughts by writing down a list of bullet points about your research visions and the gap between current literature and your vision. They do not need to be in any order as they only serve to your needs. If you are unsure of how to motivate your audience, you can refer to the introductions of the key literatures where your proposal is based on, and see how your proposal fits in or extends their envisioned pictures. Another exercise to consider is to imagine: “What might happen if your work is successful?” This will motivate your audience to understand your intent. Specifically, detailed contributions to help advance your field more manageable to undertake than vague high-level outcomes. For example, “Development of the proposed model will enable high-fidelity simulation of shear-induced crystallization” is a more specific and convincing motivation, compared to, “The field of crystallization modeling must be revolutionized in order to move forward.”

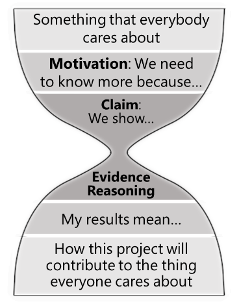

- Structure your background through the Hourglass Model. A nice way to structure your background section is called the Hour Glass Model. The model helps to motivate and guide the audience to the specific problem you are trying to solve. To create a hour glass, (a) start with a general problem that people care about (reduce global pollution, end world hunger, etc.). (b) Follow your general problem with what are the research that have attempted to solve this problem, and what are the gaps that needs to be filled to solve this problem. (c) From the gaps, identify your plans to contribute to the field and narrow the gaps. (d) Finally, refer back to the general problem to pinpoint the impact of your research on the problem.

- Research Plan.

- Break down aims into tractable goals. The goal of your research plan is to explain your plans to approach the problem that you have identified. Here, you are extending your specific aims into a set of actionable plans. You can break down your aims into smaller, more tractable goals whose union can answer the lager scientific question you proposed. These smaller aims, or sub-aims, can appear in the form of individual sub-sections under each of your research aims.

- Reiterate your motivations. While you have already explained the purpose of your work in previous sections, it is still a good practice to reiterate them in the context of each sub-aim that you are proposing. This will inform your audience the motivation of each sub-aim and help them stay engaged.

- Describe a timely, actionable plan. Sometimes you might be tempted to write down every area that needs improvement. It is great to identify them; at the same time, you also need to decide on what set of tasks can you complete timely to make a measurable impact during your PhD. A timely plan now can save a lot of work a few years down the road. Plan some specific reflection points when you’ll revisit the scope of your project and evaluate if changes are needed. Some pre-determined “off-ramps” and “retooling” ideas will be very helpful as well, e.g., “Development of the model will rely on the experimental data of Reynold’s, however, modifications of existing correlations based on the validated data of von Karman can be useful as well.”

- Point your data to your plans. The preliminary data you have, data that others in your lab have collected, or even literature data can serve as initial steps you have taken. Your committee should not judge you based on how much or how perfect your data is. More important is to relate how your data have informed you to decide on your plans. Decide upon what data to include and point them towards your future plans.

- Name your backup plans. Make sure to consider back-up plans if everything doesn’t go as planned, because often it won’t. Try to consider which part of your plans are likely to fail and its consequence on the project trajectory. In addition, think about what alternative plans you can consider to “retune” your project. It is unlikely to predict exactly what hurdles you will encounter; however, thinking about alternatives early on will help you feel much better when you do.

- Safety. Provide a description of any relevant safety concerns with your project and how you will address them. This can include general and project-specific lab safety, PPE, and even workspace ergonomics and staying physical healthy if you are spending long days sitting at a desk or bending your back for a long time at your experimental workbench.

- Timeline. Provide a traceable set of time, structured goals, and deliverables. This will help you to organize your time, give you a sense of how your project will evolve over time, and, most importantly, allow you to determine when can you graduate!

- Create the details of your timeline. The timeline can be broken down in the units of semester. Think about your plans to distribute your time in each sub-aims, and balance your research with classes, TA, and practice school. A common way to construct a timeline is called the Gantt Chart. There are templates that are available online where you can tailor them to fit your needs.

- References. This is a standard section listing references in the appropriate format, such as ACS format. The reference tool management software (e.g., Zotero, Endnote, Mendeley) that you are using should have prebuilt templates to convert any document you are citing to styles like ACS. If you do not already have a software tool, now is a good time to start.

Authentic, annotated, examples (AAEs)

These thesis proposals enabled the authors to successfully pass the qualifying exam during the 2017-2018 academic year.