Criteria for Success

- Center you and your qualifications as a researcher.

- Articulate why your research is a valuable contribution to your field.

- Demonstrate critical thinking and maturity regarding your methods and analysis approach.

- Engage in an extended productive technical discussion with the faculty audience about your work.

Message and Purpose

The purpose of the doctoral qualifying exam is to demonstrate that you possess the qualities required to complete the PhD. This includes “mastery of the research discipline coupled with ingenuity and skill in identifying and solving unfamiliar problems” as stated in the Graduate Guide (2020-2021 edition) [http://meche.mit.edu/sites/default/files/MechE_Grad_Guide.pdf ]. This CommKit article focuses on the presentation portion of the Research Qualifying Exam (RQE) though many of the concepts can be applied to the oral subject exams as well.

You are an essential element of your research talk. Unlike many academic talks you may have given before, the focus extends beyond your results and is more about your capacity as a researcher. In this article we will discuss how you can successfully scope, create and deliver a talk that communicates your abilities.

Audience

The audience will be professors in your chosen subject area. They will be familiar with the broader field but not your specific problem. Use best practices of technical communication when introducing your research including: define technical jargon specific to your research, use analogies to explain unfamiliar topics.

Choosing your topic

Present research that will let you tell a complete story about your qualifications. This may be work from your masters degree at MIT or another school, or it can be preliminary work towards your PhD. If you are in doubt, ask your advisor or other professors in your potential RQE subject if they believe your work is a good fit. This will help ensure you meet the expectations of your audience and present the best case you can. Since the goal of the RQE presentation is to demonstrate your personal qualifications, it is OK if your presentation does not align with your current research (you have committee meetings for that once you pass Quals!)

Structure

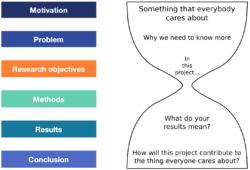

Use the ‘hourglass’ concept to structure your RQE presentation: start broad to motivate the problem, narrow to specific details in the middle, expand back out to the work’s significance in your field. Spend enough time in the narrow (detailed) part of the hourglass to demonstrate your aptitude as a researcher.

Typically, these talks are ~20-30 minutes long with ample time for questions. (Time limits can vary year to year so check the Graduate Guide and make sure you meet the current expectation.) Use your time wisely to create a cohesive, logical presentation that does not overwhelm the audience with superfluous information. It is not a race to see how much you can fit into 30 minutes. Be selective in your figures and language and use appropriate redundancy to guide your research narrative.

Introducing your research

This will be the most general part of your presentation. Clearly explain why the problem is important, what the potential challenges are, and the potential impacts.

For the RQE presentation it is often more important to highlight the state of the field than it would be in a presentation to your lab group or at a conference of researchers in your subfield. Do not expect the professors in your audience will be familiar with all the nuances of your subfield, or what gap your work is aiming to fill. By articulating how your work fits into the scientific landscape, you show that:

- you are familiar with current work,

- you understand what the challenges are in your chosen approach, and

- your contributions matter to the field.

This sequence of slides concisely and impactfully presents the top of the hourglass, while also emphasizing the researcher’s contributions early on (slide 6). Slide courtesy of Maanasa Bhaat. Fluid Mechanics RQE, Jan 2021.

Methods and results

Place more weight on methods (and less on results) than a conference-style technical presentation. Be sure to spend time presenting your research design and your rationale for any chosen methods. Your methods should be well reasoned and scientifically sound, but after all, this presentation is about you as the person behind the research.

Whether or not you have results to show, you should be able to explain why your results (will) matter. Why is the problem significant in your field? How are your methods going to provide information that is different from what exists already or fills the knowledge gap you identified? Link your results back to your motivation and problem statement.

Highlight your contributions

Highlight your research contributions from the start of the presentation. A “contribution” could address any part of the stated goal for the RQE, demonstrating your:

“mastery of the research discipline coupled with ingenuity and skill in identifying and solving unfamiliar problems”

While publications, presentations and patents are external signals of your achievements, there may be other examples that meet this goal as well. If you are light on formal academic credentials so far in your research, alternative achievements might include: collaborations you have led with other labs, competitive awards you have received, experimental set-ups that you created or (yet) unpublished results. Be selective with non-traditional achievements, though, as this is a presentation not a resume review.

Get comfortable using the word “I” instead of “we.” Unlike most technical presentations, in the RQE you will be presenting on behalf of yourself only, not your research group. Be truthful about what parts of the research you did not do, but use “I” at every opportunity it is appropriate.

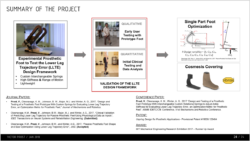

Consider ‘bookending’ your presentation with a single slide summary of your contributions at the start and end. At the start, this allows you to clearly differentiate where previous work ends and your ingenuity begins. For any collaborative efforts, clearly identify what you did. At the end of your presentation, conclude with your goals in mind. It may be useful to have your final slide to reiterate your contributions (instead of thanking the audience or asking for questions). Given that the goal of the RQE is to show your research qualifications, repeating the information as the final slide will complete the narrative you told throughout your presentation.

A final slide showing your contributions lets you highlight publications, patents, and/or awards while also reminding the audience what you have covered and prompting questions. Slide courtesy of Victor Prost. Machine Design RQE, Jan 2018.

The supplemental materials linked at the bottom of this page have additional annotated RQE slides from all areas of the hourglass.

Visual Presentation

See the full MechE CommKit article on Technical Presentations (https://mitcommlab.mit.edu/meche/commkit/technical-presentation/ ) and Virtual Presentations (https://mitcommlab.mit.edu/meche/commkit/virtual-presentations/) for more details. This slideshow presentation [http://www.writing.engr.psu.edu/speaking/rethinking_psu.pdf] from Pennsylvania State University’s writing center has additional visuals as well.

Improve clarity of your message by…

Providing a clear structure for your presentation

“Visual signposting” and slide consistency will make the information easier to digest. A visual signpost is a way for you to remind your audience what point you are making, and remind them where in the presentation you are. Tools such as a visual outline or progress bar in the slide header/footer can be used for this purpose. Visual outlines (with queue images or diagrams) can also be a good way to reiterate your key contributions!

Throughout your slides, follow a clear format. For example: try to use a consistent slide template and highlight key results with the same color or placement on the slides. These strategies will allow the audience to focus on your message without the distraction of decoding each slide format individually.

A progress bar keeps your audience anchored in the sequence of your presentation. This outline also calls out four specific areas the researcher will address later. Slide courtesy of Hilary Johnson. Machine Design RQE, May 2018.

Take a look at the supplemental information linked at the bottom of this article for some annotated examples!

Including one ‘claim’ per slide

This claim can often be used as your title. Avoid introducing a concept, method, plot and key result all in one place. Ask yourself what the most important (single sentence) take away is from a given slide, and have the rest of the slide support the claim. Evidence to support the claim should be succinct text or a visual.

The first slide of this pairing introduces the audience to the context, variables and coordinate systems present within the problem. The results are presented on a second slide and the conclusion has a (literal) ‘big red box’ around it to focus the audience even more. Slide courtesy of Rashed Al-Rashed. Structures RQE, Jan 2018.

Maximizing the signal-to-noise ratio

Many slides can be improved by cutting out visual distractions. Removing text is one way to reduce noise. If you have too many written words, your audience may entirely ignore what you are saying to them!

The example below is from the CommKit article on Technical Presentations (https://mitcommlab.mit.edu/meche/commkit/technical-presentation/ ). Notice the elements discussed above as you look over these slides.

Quite a few elements make this slide pairing successful, including: 1) a single claim is introduced as the title of each slide. 2) Signal to noise is maximised by presenting an expected trend to introduce a concept before presenting ‘messier’ real data. 3) The layout and format are consistent between the first slide (introducing the *type* of data collected) and the second (with messier, real data). 4) The key finding on the second slide is highlighted in red.

Apply these principles to figures too

Figures are a visual way to support the claims, evidence and reasoning you present verbally.

Align your figure message to one of the motivating areas of the RQE: your ability to perform significant research into previously unknown topics.

While figures in a journal article may include many concepts at once, figures used in a presentation should support your narrative and overall message. A figure can be used to show a gap, a significant achievement, or a new way of thinking. Which purpose does each figure you have included fulfill?

Consider schematic representations

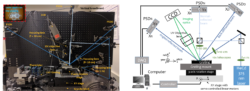

Extraneous details in photographs can distract from the main takeaway of the visual. Consider the signal you are trying to send with a given diagram, and what parts of it may just be noise.

(The metaphor of “signal-to-noise ratio” comes from Jean-luc Doumont’s book Trees, Maps, and Theorems.)

Photographs can show your creativity or expertise in setting up experiments. By contrast, diagrams can emphasise the flow of information (eg power, light, data) and individual components. Comparison courtesy of Jungki Song.

See the full MechE CommKit article on Figure Design here (https://mitcommlab.mit.edu/meche/commkit/figure-design/)

Oral Delivery

Anticipating and Fielding Questions

The question and answer portion of the Qualifying exam presentation is almost as long as the presentation itself. There is no way to know exactly what you will be asked but you can prepare and practice strategies to respond effectively. And remember, detailed questions are a good thing – they mean the audience was interested and paid attention to the details.

Think about your audience

Tailor your talk to the professors you know will be in the room, but don’t go overboard. Do not try to ‘game’ the audience by presenting only what you think certain professors would like to see. You will present yourself best if you present a genuine and comprehensive story about the work you have done.

However, be prepared for a range of questions in the discussion portion. Think about your research in the context of frameworks and methods used throughout your field as professors may ask you about this. Does Professor X apply machine learning in your domain? You may want to prepare a back up slide with your assumptions or initial conditions for the models you used. Is Professor Y an experimentalist and you presented mainly theory? Maybe anticipate a question on how your research could transfer into experiments.

Actively listen to questions you are asked

Listen to the whole question before starting to respond. Avoid preemptively flipping through your slide deck while the person is still posing their question as this might cause you to miss what they are really asking.

Check your body language, eye contact, etc. Direct your attention to the person posing the question both physically and with your ears.

Be empathetic and listen for what the questioner is really asking. For example: before answering a detailed question that seems unrelated, consider if you presented your problem formulation clearly enough. Perhaps the questioning is really indicating they missed a more fundamental piece of information in your presentation. Reflecting on and understanding the intent of a question can also be achieved through structuring your responses…

Structuring your responses

Ideally, the question and answer portion of the presentation should flow naturally as a very engaging conversation between you and the professors in the audience. For some people this will come easily, but for others it might be a daunting task in the moment. Framing each response with the four steps outlined here can help you slow down and answer any question with composure and clarity. First, verify that you understand the question topic/intent. Next, pause and think. Consider what you will say before you start rambling without purpose. A shorter, more concise answer will often go further in demonstrating your understanding than a longer answer. Once you respond, follow up with the person who asked the question to confirm you have answered it. Repeat this cycle as often as necessary.

The framework of verifying the question, reflecting before you begin to speak and then responding appropriately will often create a natural dialogue with productive follow up conversation between you and the audience.

This flow works in many circumstances.

- If you don’t understand the question…

- Clarify the intention of the question.

- Rephrase what was asked in your own words.

- If you don’t know the answer…

- Consider if the question is meant to stretch you beyond the scope of your work, or whether it is to test your depth of knowledge.

- Identify the most important aspects or alternatives.

- Articulate why it is out of scope for your research (if it is).

- Say true things and be honest about your limits.

- If the audience disagrees with something you have presented…

- Identify the specific area of disagreement: is it a method? A calculated result? An interpretation of your data?

- Think about why they believe it is wrong or could have been done better.

- Present your counter reasoning.

- Consider and discuss if this could be an alternate path forward in your research.

Questions may come up during your presentation as well. If you think you will answer the professor’s question in a few slides, this framework can still be useful. Acknowledge the question when you are asked but defer it with something like: “I believe I will answer that shortly. Do you mind waiting until then?” Once you think you’ve answered their question, go back and verify that your response was sufficient. They might have a follow up question, or you may need to start the four step cycle of responding again.

Expect to be asked questions you don’t know the answer to. Practice a graceful and thoughtful way to say you don’t know. In your ‘thinking pause’ decide what tactic you will take in replying: you could reason through something on the spot (this will show you are considering their question), or return to the knowledge gap you identified and why you believe the question is out of scope, or use the question as a springboard to discuss future work. Whatever you choose, do not try to make it seem like you know something you do not. Professors are very good at seeing through this, and that will likely cost you more points than not knowing.

Delivery should enhance the message

Amplify signal and reduce noise

To make your message come across clearly, stick to a concise “claim, evidence, reason’ structure throughout your presentation. Link new information to previous information verbally. Be mindful to not ‘over talk’ as this may distract your audience from the message you are trying to convey. Don’t put more on your slides than you plan to talk about, this is noise.

Not only what you say, but how you say it

Be aware of your normal speech patterns and how they might change the way your audience receives the message. For example, how many different ways can you say the word “seriously” so that you convey a different message each time? In the context of the RQE presentation, consider the following:

- Volume and tone that places emphasis on key points

- Pacing (often slowing down) to give your audience time to digest important points

- Diction, especially for key technical terms (e.g. from the author, how do you really say ‘Poiseuille flow’?)

- Inflection to place questions and emphasis where you intend (avoiding persistent upspeak)

- Physical movement can be distracting if overblown. Pacing, talking with your hands, and rocking can be useful ways to handle presentation anxiety, but overdoing any of them may cause your audience to lose focus on your message.

Everyone has a unique presentation style. The more you practice presenting to peers (or CommLab fellows!) the better you will be able to isolate your presentation style from ticks that others may find distracting.

COVID note: Also take a look at the Virtual Presentations CommKit article (https://mitcommlab.mit.edu/meche/commkit/virtual-presentations/) for specific advice relevant to all virtual presentations.

_____

Enjoyed what you learned here and want more? Make an appointment with a CommLab Fellow today! Fellows go through training in written, visual, and oral communication and will be able to work with you on any of the topics discussed in this article.