1. Criteria for success

A strong portfolio overall…

- Highlights your most relevant work

- Includes 3 or 4 diverse projects that showcase skills relevant to position

- Tells a story of you as a capable and experienced candidate for the application

- Clear structure to be quickly parsed

- Can also include extracurricular and volunteer experiences

- Helps recruiters learn more about your personality and passions

Each project page…

- Describes the objective of the research/design project, i.e., your high-level design requirements.

- Provides just enough technical detail to orient the reader to the project

- Explains your specific technical contribution to the project

- Emphasizes skills used or learned through the project

- Describes the results of the design, and evaluates how well it met the initial objective

- Provides visuals (photographs, renderings, drawings, graphs, …) that illustrate and support your technical work

2. Purpose

Your portfolio complements a text resume with visual information that clarifies technical details of design projects and engages the reader in your work.

The portfolio should present a narrative of you as a capable, experienced candidate for the position you’re applying for. Each application you submit should have a portfolio tailored to the needs of the specific role. In an interview, you will not have time to go over everything, so pick your three or four most relevant experiences that support the narrative you want to present.

3. Analyze your audience

Each time you submit a portfolio, you should think about who will be reading it and what they want in an applicant. If aerospace engineers will be evaluating your application, then technical design details will be well-received and understood. But if you’re applying to be the sole aerospace engineer within a startup, your portfolio might need to be revised to provide more background that orientates the readers, and just enough technical detail to demonstrate you know what you’re doing.

Similarly, consider the role you’re applying for, and which of your skills are most valuable for them. Format your portfolio to illustrate those skills up front.

For example…

- If you are applying for an orbital mechanics position, put projects on flight dynamics up front. Don’t leave out other projects, keep them, just move them to the end.

- If you are applying for a professorship in a teaching college, put experiences as a TA up front and then add research experiences.

4. Context

It’s also important to consider the context of how your reader will view your portfolio. If you’re sending it in an application packet, more text is ok. But if you’re providing a handout in an in-person interview, consider cutting most of the text – rely on your visuals to catch their eye and lead into conversation. Your figures should reinforce your words.

Finally, consider how quickly your portfolio will need to convey its message in different use cases. Some approximate guidelines:

- In-person: Expect the interviewer to skim each project for something that jumps out at them to start discussion. They may also reference it later when evaluating you further or comparing you to others.

- Submitted online or mailed in: Expect the reader to spend a bit more time going through each page since you’re not there to answer questions.

- Web: Expect a reader to click through your web portfolio skimming text and looking for catchy graphics. Make sure they can easily navigate around your site and find projects that are relevant to them.

In all cases, reviewers may look at each project for only 30 seconds to a minute, so keep it concise!

5. Structure diagram

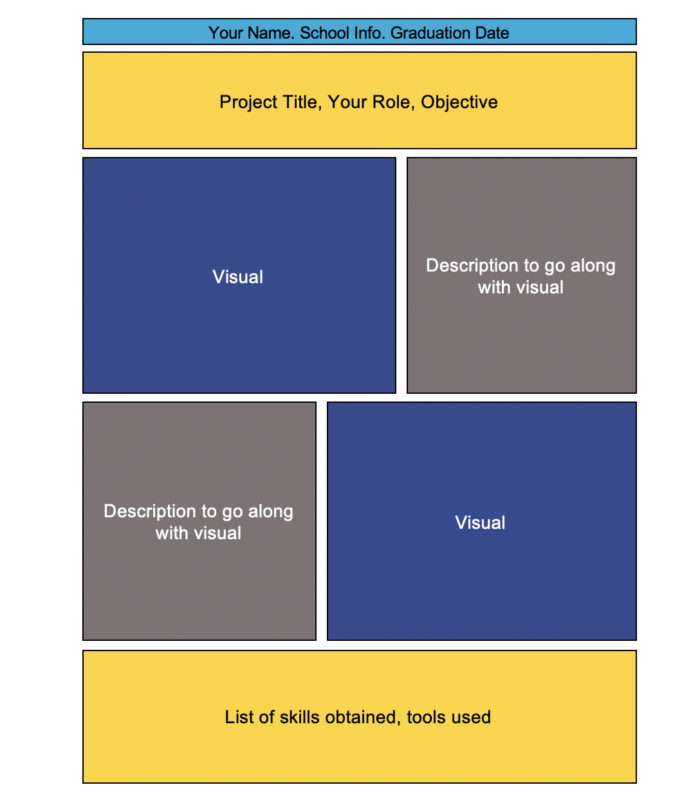

Your portfolio should contain one project per page. If you’re not sure where to start, this diagram can be a good jumping off point. However, each project is different so this is by no means a defining layout.

Example structure diagram of a project page for an engineering portfolio.

Here are some good rules of thumb to follow when designing a project page:

- The majority of the page should be visuals (no one is going to read a paragraph of text)

- All text should be quick statements and bullet points or lists

- The objective of the project should be clearly defined, as well as your results

- If a group project, your specific contributions should be made clear

- Your name should be on the top of each page

6. Best Practices

6.1. Select and order your projects appropriately

If a reader is only glancing at your portfolio, what would you want to make sure they see? Spend some time deciding which projects will be most compelling and engaging. If there is a project that you’re most proud of, or that looks the best, move it towards the front of your portfolio. Similarly, if you’re applying for a job that wants specific skills, move the most relevant projects to the front.

TIP: Keep a master portfolio with all of your projects, and select different projects to tailor a smaller portfolio for each application or submission.

6.2. Select visuals that contextualize and summarize your contributions

Depending on the project, use two to six visuals to demonstrate the most important parts of the project. Select visuals that support what you want your reader to understand about your technical abilities and design process. For instance, if your system met stringent requirements to support your objective, a plot of some performance metric can help emphasize a successful design. But if you calibrated a piece of equipment with standard methods that do not highlight your technical skill, that calibration curve is probably not a good choice.

Don’t choose redundant visuals. Make sure that the visuals illustrate different aspects of the project and of your contributions.

To help orient the reader to how your work fits into a larger system, use a mix of system-level and subsystem-specific visuals (schematics, pictures, renderings, drawings). As a rule of thumb, motivate your contributions to a subsystem by first showing the whole system.

6.2.1. What if my project visuals are ITAR, SBU, proprietary, or have other restrictions?

We know that many AeroAstro students work with ITAR (International Traffic in Arms Regulations) or SBU (sensitive but unclassified) information that cannot be shared in a public portfolio. Always talk to your manager/advisors if you work with sensitive material on what is allowed to be shared. Mention you want to put your work in a portfolio and ask what aspects of the project can be shared, sometimes they can make suggestions for material that is safe to display.

If all visuals are restricted, mention in your portfolio that the work was ITAR to explain the lack of photos. Instead of using actual pictures or renders, you could make your own diagrams to explain your work progression and responsibilities while avoiding design details. Even arranging your text creatively and using emphasis can have a similar effect as a visual.

6.2.2. Declutter and annotate visuals for clarity

- Photographs should be high-quality and staged. Make sure they are well-lit, sharp, and free of clutter. It is also a good idea to take photographs throughout your work process to capture the stages of development and experimentation. Check out this blog post on photographing technical projects for some helpful tips and tricks.

- When using visuals of complex systems, avoid busy backgrounds or complex foregrounds. Consider cropping or masking parts of the image to draw attention to the most important parts.

- If you want to focus attention on a particular subsystem, consider inserting a close-up of that subsystem into a block diagram or schematic of the larger system.

- Consider annotating visuals to draw attention to specific features or concepts that relate to your technical contributions. For instance, if you worked on a specific subsystem, highlight its place within the larger system. If your work involves precision design or high loads, illustrate the critical forces that are relevant.

- Don’t make visual elements too small. Make sure the key parts are comprehensible when printed.

6.3. Describe your design objectives

Answer the questions:

- What are you designing?

- Why does it matter? Who does it help?

- What requirements does it need to meet?

- How did/will you evaluate performance?

Since the portfolio is a supporting document with a fairly small amount of text, don’t spend too much text establishing the background or global scope of your project (unless this portfolio will be reviewed by a non-technical audience). Instead, write the requirements/objectives in a way that lets you highlight your technical contributions.

6.4. Highlight important technical details of your design process

- Answer the questions: What did you actually do to achieve the goals? What was your process?

- Use strong action verbs that describe what you did.

- Strong Verbs: designed, machined, analyzed, compiled, organized

- Weak Verbs: used, did, studied, helped

- For group projects, describe your role within the group with something like the phrase “I was responsible for…”

6.5. Evaluate the performance of your design

Did it work? Did you win anything for this design? Let the reader know what came of all the work you did. If you realized afterwards that it didn’t work in some way, reflect on what went wrong or what you learned for the next design iteration.

TIP: If you won an award for your work, consider showing a photo of the award to catch the reader’s eye, instead of just mentioning it in text.

6.6. Consider creating a web portfolio as well

Many websites now offer templates or services for engineers to create digital portfolios. An online presence can be very helpful when looking for jobs, and supports more multimedia formats than a print portfolio. However, make sure that the information that you provide in a web portfolio is just as selective and clearly organized as you would make it in print. Don’t overwhelm your viewer with too many projects or a complex layout.

At the end of the day, you should still maintain a print-ready portfolio that you can submit with your resume and bring to interviews.

7. Annotated Examples

7.1 Work and Research Portfolio

Strengths:

- Simple and clear cover page with necessary information and a creative layout

- Contains full name, email, school, major, expected graduation year

- Project pages use the same layout to create structure and consistency

- Mixture of research, internships, class projects, and personal projects to show range and personality

Areas for Improvement:

- Within text, add more emphasis to key words via bolding, underlining, or highlighting to create a visual hierarchy

- More graphics and larger images to catch the reader’s eye

- Less text on project pages so the important information is clear and a reader is not overwhelmed by too much content

- Someone should be able to skim each project page in ~30 seconds and understand your contributions

7.2 Engineering Portfolio

Strengths:

- Simple cover page with clear and adequate contact information

- Contains full name, email, school, major, expected graduation year

- Project pages emphasize individual contributions and how they fit into the larger picture

- So the reader knows exactly what YOU did and why

- Images on project pages have helpful captions so the reader can understand the visuals alone

Areas for Improvement:

- Table of contents could include skills obtain or tools used for each project to help orient the reader as to what projects to look at

- Every page needs at least one or two visuals to catch the reader’s attention

- Less text on project pages so the important information is clear and a reader is not overwhelmed by too much content

- Someone should be able to skim each project page in ~30 seconds and understand your contributions

To get started or receive feedback on your portfolio, make an appointment with us. We’d love to help!

Acknowledgments:

This content was adapted by the AeroAstro Comm Lab from an article originally created by the MechE Comm Lab, MechE Portfolio CommKit by Thanasi Athanassiadis

Thank you to Evan Kramer, Harsh Bhundiya, Brian Mernoff, and Chiara Ricci-Tam for their contributions.