Criteria for Success

- Clearly articulate your brand.

- Demonstrate the impact of your past work.

- Show that you are credible to carry out your proposed future research.

- Articulate the importance of your research vision.

- Match the standards within the department to which you are applying.

- Show that you are a good fit for the position.

- Polish. Avoid typos.

Structure Diagram

The typical structure and length of research statements vary widely across fields. If you are unsure of what is typical in the field where you are applying, be sure to check with someone who is familiar with the standards.

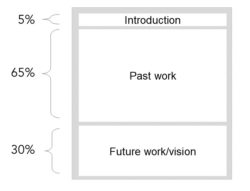

In electrical engineering and computer science, research statements are usually around three pages long with a focus on past and current work, often following the structure in the diagram below.

Identify Your Purpose

Your cover letter and CV outline your past work and hint at a general direction of your future work but do not go into detail. Therefore, the purpose of a research statement is to emphasize the importance of your past work and describe your research vision. Both your past/current work and future work presented in the research statement should reflect your branding statement.

In EECS, faculty research statements focus on past/current work. However, it is important to also include your vision for the future, which should build on your previous work. This statement should convince the committee that your future work is important, relevant, and feasible. The future work section should go beyond direct extensions of your doctoral or postdoctoral work; it should cover a 5-10 year span. Proposed future work should show scientific growth and convince the committee that you propose strong research directions for your future group. Your research statement can also include possible funding sources and collaborations.

Analyze Your Audience

Your audience is a faculty search committee, which is made up of professors from across the department, not just the ones in your research area. A typical search committee member is probably very busy reviewing lots of applications, and hence may not read your statement in depth until you make it to later rounds of the hiring process.

Knowing details of the job posting and what the faculty search committee is looking for will help you tailor your statement. If the call is for a specific research area (e.g., language processing, bioinformatics, algorithms, machine learning, systems), it is beneficial to motivate and emphasize the importance of your work in the language of that area whenever possible.

Skills

Structure your statement

Although there is usually no mandated structure for a research statement, it can be very helpful to a reader if the content flows naturally.

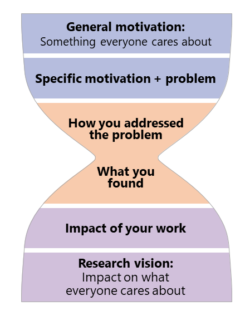

Use the hourglass concept. It makes a compelling introduction if a research statement presents motivation starting from the high-level picture and then zooms in to the main topic(s) of research. This is helpful for two reasons. First, a research statement is typically read by committee members from several research areas, so starting with a high-level picture gives members a gentle guidance to the meat of a work. Second, providing general motivation helps in showing how different pieces of research fit in a big puzzle.

After talking about specific results, the story typically zooms back out by discussing impact and future directions. It is best if future work has some concrete research directions and also widens up to touch on a broader perspective of research plans.

The diagram below summarizes the hourglass concept and provides one potential flow of content.

Use good formatting to help retain focus. A successful research statement is typically organized into three main parts: Introduction and motivation; past work/achievements; and vision/future work. Each of these parts can be divided into subsections.

In addition, you can help a reader focus their attention on the important content by:

- making each section/paragraph title tell a message;

- using bullet points and itemization while listing;

- using bold or italics to emphasize important keywords or sentences.

Some institutions set constraints on the format of research statements, primarily constraints on length. Make sure that your research statement is tailored to the guidelines. It is helpful to prepare two versions of your statement — a long one and a short one. The short version is usually the long one stripped of many details with the emphasis on high-level pictures and ideas.

Say who you are

Your research statement tells a story about you. Think who you want to be in the eyes of committee members (e.g., a programming languages person, a machine learning expert, a theory professor) and which of your achievements you want them to remember.

Make your research statement echo your branding one. A successful research statement builds a story around the author’s branding statement. A strong point is made if past and future work are echoes of the same brand.

Successful candidates outline their research agenda before stating actual results and after providing a background. Sometimes this is done even before giving background and motivation. In the latter case, the research agenda is typically stated briefly, and then reiterated with more context after providing the background.

Show credibility for your future work by your past work

Your past work is an excellent way to illustrate that you are fit for the future work you are proposing. Refer to some of your past work when outlining feasibility of your proposed future directions. Even if you aim to change your field of research, your past experience should still serve as a justification for why you are well suited for the new line of work.

Dedicate space to your strongest results. Describe your strongest results in the most detail. If you want to mention many papers, organize them into several themes. A successful statement communicates how obtained results affect a field or a research community. Impact of papers can be shown by awards, high number of citations, or follow up papers by other research groups. A reader will have limited time to go over your statement, so make sure that the reader’s attention is spent on your most impactful work. Note that your strongest results do not necessarily have to be your most recent ones; they can even be several years old. Nevertheless, it is still a good idea to also mention some of your recent work as it shows that you have been active lately as well.

Importantly, a research statement should be a coherent story about ideas and impact, not only an overview of published articles. Hence, it is often the case that a research statement does not discuss all papers published or all work done by the applicant.

Use figures to support important claims. Consider including figures. They can be used to support your claims about your results and/or in the future work section to illustrate your research plans. A well-made figure can help the reader quickly understand your work, but figures also take up a large amount of space. Use figures carefully, only to draw attention to the most important points.

Devote time!

Getting out a job application package takes an indefinitely long time (writing, addressing feedback, polishing, addressing feedback … aaaand polishing)! Start early and invest time.

Get feedback. Your application package will be read by committee members that are not necessarily in your research area. It is thus important to get feedback about your research statement from colleagues with different backgrounds and seniority. Note that it might take time for other people to share their feedback (remember, others are busy as well!), so plan ahead.

MIT EECS affiliates can also make an appointment with a Communication Fellow to obtain additional feedback on their statements.