Criteria for Success

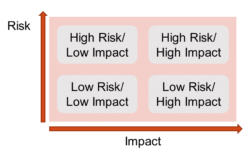

1. Decide which grants are appropriate for you. The appropriateness of a grant is based on both the topic and the balance of impact and risk. First, determine whether the grant you are applying for is appropriate for the topic of your project. Second, consider the grant and your project in terms of impact and risk balance. To do so, consider:

- What impact would successful completion of your project have on those inside the field and those outside of it?

- How likely is your proposed work to succeed?

- How can you minimize the risk? For instance, what alternative strategies can you use if your proposed methodology fails?

- What can you learn if the project “fails”?

In which quadrant is your current or future project? Which quadrant are you shooting for?

2. Follow grant solicitation instructions exactly. Be sure to adhere to requirements for font size, margins, and other formatting. Include all required accompanying documents.

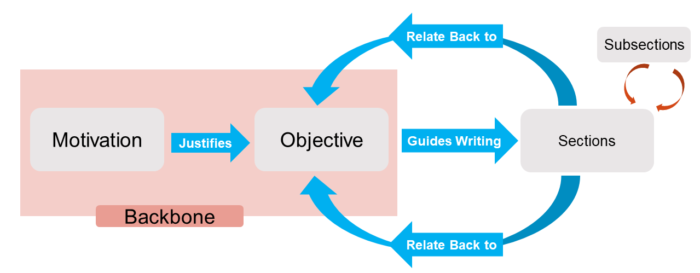

3. Make the motivation and objective clear. The backbone of any successful grant proposal includes both why the project is important and what successful completion of the project will look like.

Structure Diagram

While the section names and detailed structure will vary by grant and project, the proposal parts shown above should be thought of as conceptual components which exist in any grant.

Your motivation for proposing a project needs to be clear, and all the rest builds on that. The conceptual components above relate to each other in the following way: The impact of successful completion of the project for those inside and outside the field should be obvious. This motivation should justify the clear objective of the proposal. Everything else in the grant should relate back to the motivation and objective.

Identify Your Purpose

The purpose of a grant proposal is to secure funding. To that end, you must clearly show impact and feasibility within time and resource constraints (including potential bottlenecks and solutions). Your proposal must also be a good match for the funding source; it needs to directly address the goals of the prompt and/or the funding organization.

Analyze Your Audience

Before you start writing, consider your audience: The Reviewer.

Consider that the first thing a grant reviewer reads (e.g. proposal summary, abstract, specific aims) must give them a complete picture and be very compelling and convincing. To achieve this, be concise, but don’t be afraid to repeat the motivation, objective, or general approach where you deem it necessary. Remember that reviewers are working under time constraints. For example, it is estimated that NSF reviewers assess 10-12 proposals for a given call for proposals and spend only 90-120 mins per proposal [1]. Redundancy is good if it helps to make your message clear.

Have in mind that these are the questions reviewers will consider while reading your proposal:

- Is the problem important?

- Does the approach described fulfill the research questions? Will it work?

Consider formulating the motivation for someone in your subfield and for someone in the broader field. Ask yourself these questions as a writer and mock reviewer: Is the objective stated in one place? Is it clear and well-motivated for a person in my subfield and in the broader field? Is the work novel?

Skills

Formulate clear, appropriate motivation and objective

Let your motivation and objective be the best written sections. As the motivation and objective are the backbone of the proposal, make them very strong.

Remember that the motivation should justify the objective. Types of motivation are grant-dependent. The solution to an applied or fundamental problem may meet a clear need or fill a knowledge gap. The solution to a theoretical problem may lead to multiple applications in the future.

Convince the reviewer your objective is worth funding. It is very important to strongly make the case that the objective is both (1) impactful and (2) novel.

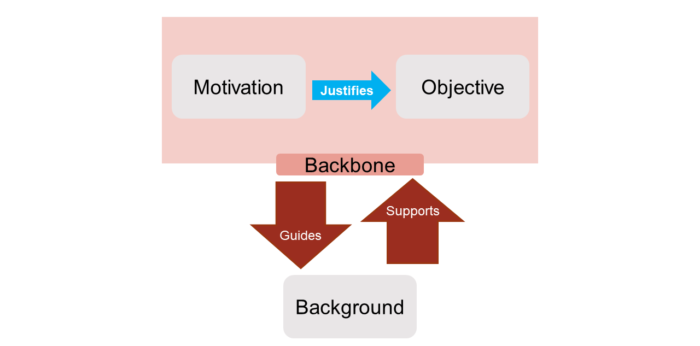

Write a relevant background

Background is not just a bunch of ideas about what people have previously done. Background material should be thought of as support for the backbone (motivation and objective). Therefore, write the background with the motivation and objective in mind.

When writing background material, ask yourself, what minimal background does the reviewer need to know? Make sure that the following are made clear:

- What is the context in which your problem is motivated?

- What is the gap you are trying to fill? The literature review should not be random but rather should specifically cater to filling this gap and leading the reviewer to your motivation and objective.

- What is your approach?

Write an appropriate approach

The approach should contain how you would carry out meeting your objective. Therefore, the approach should be tightly linked to your objective. The approach can sometimes be expressed as aims. When this is the case, specific aims should not all be interdependent.

Overall, this section should address:

- Why is this approach well-suited to your objective? OR How does this approach relate back to your objective?

- Is the approach feasible within the grant’s timeframe?

- Why are you not using an alternative approach?

- Expected bottlenecks – what will you do if this approach fails?

Final Remarks

Note that the proposal parts (Motivation, Objective, Background, Approach, etc.) discussed here do not necessarily correspond to modular or separate sections in every grant proposal. The structure of each proposal will be grant and project dependent. Rather, these parts should be thought of as conceptual components which should exist in any grant.

Overall, remember that every component in a grant proposal should be directly or indirectly related back to the objective and motivation. The backbone of your proposal should always be present and apparent.

References

[1] Lesiecki, et al., How to Write a Winning NSF Proposal

https://math.mit.edu/services/grants/documents/winning-nsf.pdf