Criteria for Success

The Introduction should have enough general background for everyone in the audience to understand the topic of your project.

Your Introduction should answer the following questions:

- Problem statement: What problem does this paper solve? (Or, what question does it answer?)

- Motivation: Why is this an important or hard problem?

- Solution: How does this paper solve the problem?

- Contributions: What are the new contributions of this paper?

Depending on your specific subfield and paper, some of these questions might be obvious; all of them are important to prepare and convince the reader to continue reading.

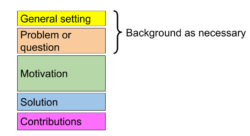

Structure Diagram

The structure and length of the Introduction varies widely by subfield, for example between electrical engineering, theoretical computer science, machine learning, and systems. Here is one possible structure, for a typical paper in systems:

Read papers from a conference or journal you might submit to in order to get a sense of what to put in the Introduction vs. other sections. For example, in some subfields the Introduction includes the background needed to understand the rest of the paper, while in others background would be in a separate section. In general, readers from outside the subfield may read only the Introduction, so it should be targeted at a broader audience than the rest of the paper.

Identify Your Purpose

After reading your Introduction, the reader should know what problem your paper tackles, appreciate why solving it is important, and grasp what solution your paper presents.

Many readers will not read past the Introduction and are reading the paper to understand what has been accomplished and why rather than how it was done (which the rest of the paper will talk about). Because of this, the last question – what is the contribution of the work? – is the most important to answer.

Analyze Your Audience

Your audience includes researchers with a variety of backgrounds, ranging from specialists who might want to reuse your work to newcomers reading your paper as an Introduction to the broader field. The further from your specific area, the more a reader will benefit from a well-written Introduction.

Reviewers are obliged to review the entire paper. Even so, the Introduction can get reviewers excited about the rest of the paper, which will help frame your work in an accurate and positive light.

Focusing on outside readers will chiefly affect two parts of the Introduction:

- It will increase the motivation’s breadth. For an insider audience, you might begin with a summary of known techniques or approaches to solving a specific problem in your field. For a more general audience, you might start with a higher-level motivation for the problem you are solving. How does it fit into the broader research goals of your field?

- It leads to a less technical motivation. The more basic the question posed in the problem statement, the more people will care about it. Take the time to identify the simplest, most fundamental question your work answers. More technical questions will attract a smaller, more specialized audience. If you make your results seem less general than they actually are, you immediately lose part of your potential audience.

Breadth, length, and comprehensiveness of the Introduction are highly dependent on your specific field and on the journal or conference you submit to. Analyze successful papers from your target venue and aim for a similar level of generality.

Skills

Develop a story

The Introduction sets up a story for the paper, a narrative with a problem statement and motivation to your contributions. To come up with this story, work backwards: start with what you did, come up with a list of research contributions from that work, then determine what problem or question these contributions address, and finally motivate the importance of this problem or question. If you have multiple options, focus on the most compelling motivation (a problem your audience will care about) and a problem that aligns well with your contributions.

Some useful questions to ask yourself while coming up with a story include:

- What problem does your solution completely address? The motivation can be broader than the problem statement, but readers expect the paper to completely address some problem.

- What aspects of your solution are novel? What aspects are the most interesting?

- What would a fellow researcher use from your work?

- What is the gap between existing work and yours?

Orient the reader

Start off with something everybody cares about. Then give specific background to give the reader a sense of past accomplishments and competing approaches, giving credit by citing previous work. Motivate why this specific problem is worth solving.

See the annotated example (Argosy) for an example in which a relatively long background was necessary.

Give just enough technical detail

The Introduction should have the minimum technical detail necessary to understand the problem and contributions. Defer as much as possible to the rest of the paper, possibly moving technical background to a dedicated section. The Introduction should adequately motivate the work since readers use it to determine whether to read more and to situate the rest of the paper.

See the annotated example (Karaoke) for a good example.

Content adapted by the MIT Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Communication Lab from an article originally created by the MIT Biological Engineering Communication Lab.