Imagine two people on the phone. One is in Boston and says it’s “9 am.” The other is in Paris and says it’s “3 pm” (or more likely, “15 h”). Who is right? Obviously, time zones are universally recognized and we accept that this discrepancy isn’t a matter of opinion but of location. Both people are right and they know it. Now suppose they are collaborating on a document. The Bostonian believes it’s best to state your position right at the beginning, whereas the Parisian insists on gradually building up their argument. Who is right? Is it now a matter of opinion, or is it still a matter of location?

While some location-based differences are obvious (language, currency, electrical outlets), others can be veiled by people’s ability to speak the same language. Writing, as a discipline, is among these less visible differences that can cause unnecessary frustration. I certainly wish someone had warned me about this! When I landed in Boston as an international student many years ago, I immediately adjusted my watch to the local time, but didn’t know to adjust my communication techniques to local best practices.

From Rousseau to Thoreau

Like everyone at my new, American high school, I was enrolled in an English writing class. Unlike my classmates, however, I was equipped with the best form of education that I knew (then): the French system. I could write well, and my score of 18/20 on the written portion of the French baccalaureate exam validated my track record. Yet, my English teacher felt that my writing needed work.

Mr. M’s impatience as a reader didn’t match his otherwise relaxed attitude. He often jotted, “What’s your point?” next to my opening paragraphs. “Well, that’s the introduction,” I thought. “Of course there isn’t a point; I’m getting to it!” On my worse days, I wondered if he knew how to write! Despite going from writing about Rousseau and Descartes to writing about Thoreau and Franklin, I never considered that Mr. M’s comments could stem from a cultural difference in writing strategy and not a deficiency in my (or his!) writing ability. After a few months of struggle, I swallowed my pride and gave in to his methods—without understanding his reasoning.

Different countries, different writing approaches

Fast forward to when I joined NSE to start a Communication Lab. After many years of academic writing in the US, I found myself chatting with a French international student. We exchanged stories of writing in lycée (high school) and when he casually mentioned “the” writing process, it finally struck me that writing is taught differently in different countries!

It feels silly to not have realized this sooner, and yet… People who study culture often tell the story of a fish being asked, “How’s the water?” and the fish answering, “What’s water?” Similarly, when writing is taught in classrooms around the world, students and teachers might unconsciously assume that their audiences share their cultural norms—they live and breathe within these norms and don’t see them as anything peculiar. Also, outside the US, English is usually taught by non-native speakers so students (like myself) might learn to write elaborate English essays using native (French) methods.

What comes first: the “how,” the “why,” or the big picture?

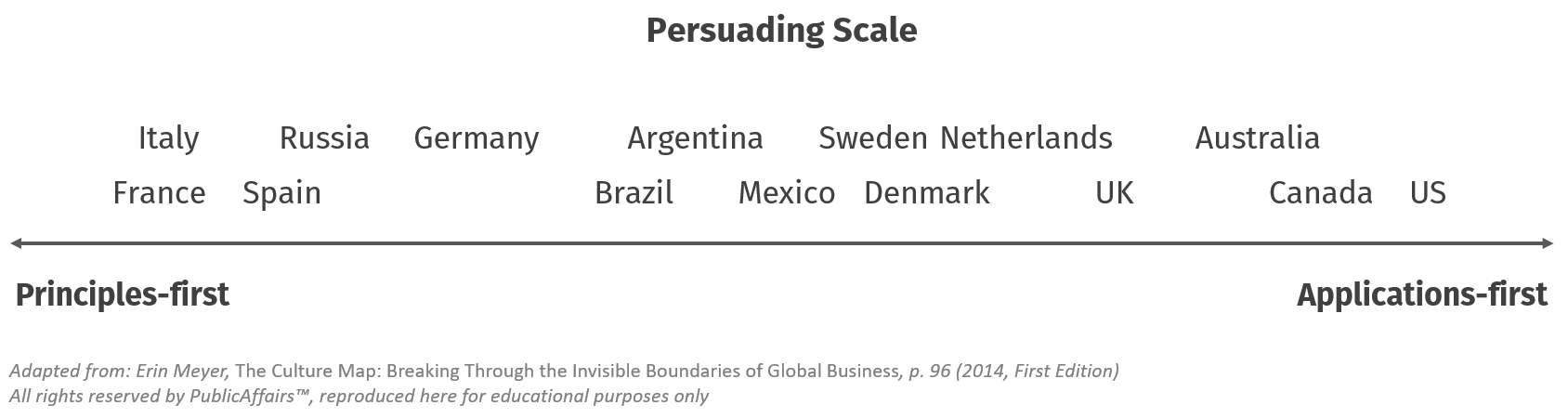

Our hypothetical Bostonian and Parisian collaborators disagreed on what should come first: the point (“why”) or the reasoning (“how”). Knowing that there are cultural differences in communication is a good start. After that, there are tools like Erin Meyer’s book The Culture Map: Breaking Through the Invisible Boundaries of Global Business. In it, Meyer shows where different countries lie relative to one another along variables like decision making, disagreeing, and giving feedback. Here’s her persuading scale:

Tellingly enough, France and the US lie on opposite ends of that scale. France—along with Italy, Spain, and Russia—is squarely in favor of principles-first approaches, where you develop your ideas ab initio before reaching a conclusion. Without understanding the “how,” there’s nothing for the takeaway message to stand on.

On the other end of the spectrum, the US—and to a lesser degree, Canada and Australia—much prefers an applications-first approach, with a focus on the practical “why” before providing supporting evidence. Without a clear motivation, why should the reader stay engaged?

Then, completely separate from this scale is the holistic style of East Asian countries. The Chinese and Japanese often describe the environment around an issue and potential interdependencies first. Only after they have assessed the big picture will they zoom in on the specifics that interest most westerners.

Viewing communication through the lens of culture

In communication, some practices are easily traced back to cultural differences like listing one’s age and marital status on a CV (don’t do this in the US!). But many practices can be mistaken for “poor communication.” This is why, when I meet with Comm Lab clients who struggle with writing in English, I first ask them if they can write well in their native language. Their answer to that question, often, is pivotal.

My advice to non-native English speakers who work or study in the US, is to state your point right at the beginning, even if it feels counter-intuitive. Do this with your emails, your presentations, and your research proposals. You may find that your US-centric audiences will respond more favorably to this approach.

And for native speakers of English who work in a diverse group, if you find it difficult to engage with a document that otherwise has excellent syntax, this could be the result of a cultural misalignment. Being aware of this can help you be more empathetic toward the writer and lead to more fruitful next steps.

Finally, Mr. M, if you’re reading this, thank you for patiently pushing me to grow and learn. Of all the classes I took at CHS, your course is the only one for which I’ve saved all my notes.

Marina Dang is the NSE Communication Lab manager. She previously served as an ESL/ELL tutor for a local non-profit organization and enjoys discussing linguistics with other polyglots.

Published October 26, 2021