This CommKit was co-authored by Communication Fellows Linda Seymour and Craig McLean.

Criteria for Success

- Structures your work/presentation in a way that is designed to engage your audience

- Has a single overarching theme

- Uses an arch to introduce the field, define the problem, and then illustrate the resolution

- Increases your audience’s retention

Identify Your Purpose

Applying principles of storytelling to your research presentation can help your audience understand your research problem and why it is important, and lures in their attention.

An article from Harvard Business Review reports that information presented in using a storytelling format is 20 times more likely to be retained than just facts presented in a linear fashion. For researchers – presenting your research through the lens of storytelling has been shown to be an effective way to reach tactile, auditory, and visual learners.

Analyze your Audience

Tailoring your research story to your audience is important in scientific and engineering discourse, and helps you build a relationship with the audience. Analyze your audience by asking the following questions:

- Who is my audience? Think about the breadth of backgrounds in the audience (e.g. high school science students, industry experts or professors) and the relevant knowledge they have.

- Why is the audience interested? At the broadest level, identify what the audience is seeking from your work. Conference attendees may be interested in learning new methodologies or understanding the implications of your work in their field. Conversely, children in an after-school program may be looking for a role model or how to connect STEM concepts to their everyday life.

- How do I connect with the audience? A group of curious scientists might prefer a clear question with an evidence-based argument while a lay audience may need a more emotionally driven connection to the work to inspire them. Remember, your instinct may not meet the needs of your audience. Their level of familiarity with your research field will influence how you implement elements of storytelling.

After answering the questions above, determine the level of detail and semantic accuracy required to connect the audience with the subject of your work, your theme, and any protagonist(s). For example, a younger or general audience may appreciate an anthropomorphized subject (e.g. a bending beam smiling/frowning instead of deflecting) and a story told from a first-person point of view (e.g. I collected water from the Charles River and took it back to my lab to see what microbes I could find). Conversely, your thesis committee may prefer the precision of numeric values, field specific jargon and a story centered on your methodology or the samples analyzed. Finally, consider the background required to understand the story you are trying to tell. When in doubt, keep it simple and ensure that each part of the narrative relates back to the major theme; however, never overstate your contribution.

Skills

There are many techniques that you can use to describe your contribution in storytelling form – a couple of ideas are listed below.

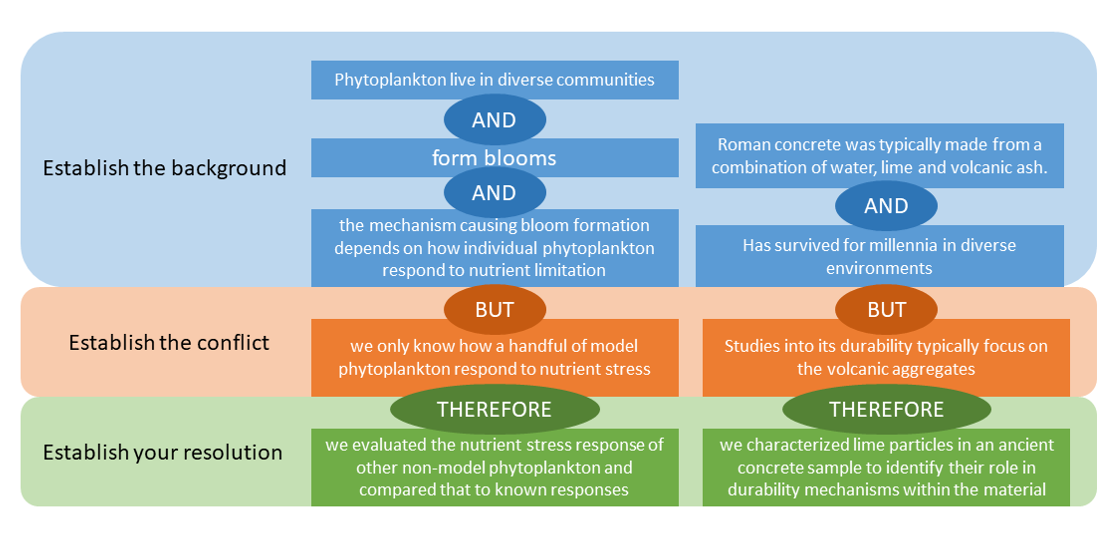

- Explain your motivation behind your work using the ABT method (and, but, therefore). As presenters, one option to create interest from the audience is to connect with them on an emotional level by adding conflict to your research story. Whether you are addressing unknown areas of your field or facing technical challenges, conflict is an inherent component of research. We can make it easier for our audience to understand it using the storytelling technique And But Therefore (ABT), developed by marine biologist and film maker Randy Olson. ABT suggests that we describe what know (AND), what we don’t know (BUT), and our attempted resolution to overcome this gap (THEREFORE). Consider the following examples:

- Tie together your work in a relatable way using the Hero’s Journey. Joseph Campbell showed that every mythical story uses a fundamental template coined as “The Hero’s Journey.” This structure is ubiquitous – you’ll find it in both movies like “Legally Blond” and ancient Greek epics like “The Iliad.” The power of the Hero’s Journey comes from its ability to structure your work into sections that provide a reader with context, conflict, and conclusion. These elements lend meaning to your work and improve your connection with the audience. Understanding this structure well enough to apply to your own work is well worth the time. Using “The Hero’s Journey” method correctly has a great deal of potential to engage your audience and help them retain the content of your work.

Additional reading

Check out the full collection of free CommKit Resources created by the MIT CEE Comm Lab team.