Throughout the year, but especially in the fall thanks to fellowship and graduate program deadlines, mentors get inundated with requests for letters of recommendation. Whether you’re applying to a PhD program or a non-academic job, these letters are an invaluable part of the application package. As one NSE professor puts it, “it’s one of the few chances for the student to be an individual and distinguish themselves from grades, GPAs, and other similar items.”

However, asking for a letter can be an intimidating prospect so we checked in with five NSE professors to learn directly from them what they would consider best practices. Aside from one or two specific tips, their advice overlapped significantly and every single professor emphasized the need for the letter to be customized for the student and the target program.

We organized the faculty’s recommendations into the 4-step guide below:

1. Get organized

Start with a bit of self-reflection. Ask yourself why you are applying to these programs. Your mentors will be able to use this information as key context when they write.

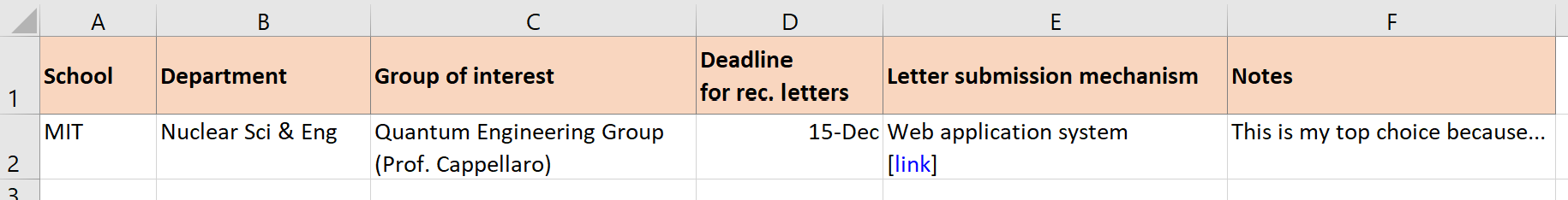

Create a spreadsheet listing the programs you’re interested in. Include respective deadlines, requirements (how many letters do they ask for?), and other important information. Faculty also like students to “have everything up front” so you may send your references a version of this spreadsheet as well, especially if you’re applying to multiple places at once. “One year, I had 5 students,” one professor wrote, “each of them applying to 10-12 schools, and 2 postdocs applying for jobs… Without spreadsheets, it would have been impossible!” Something like the table below might be a good place to start:

2. Choose your writers wisely

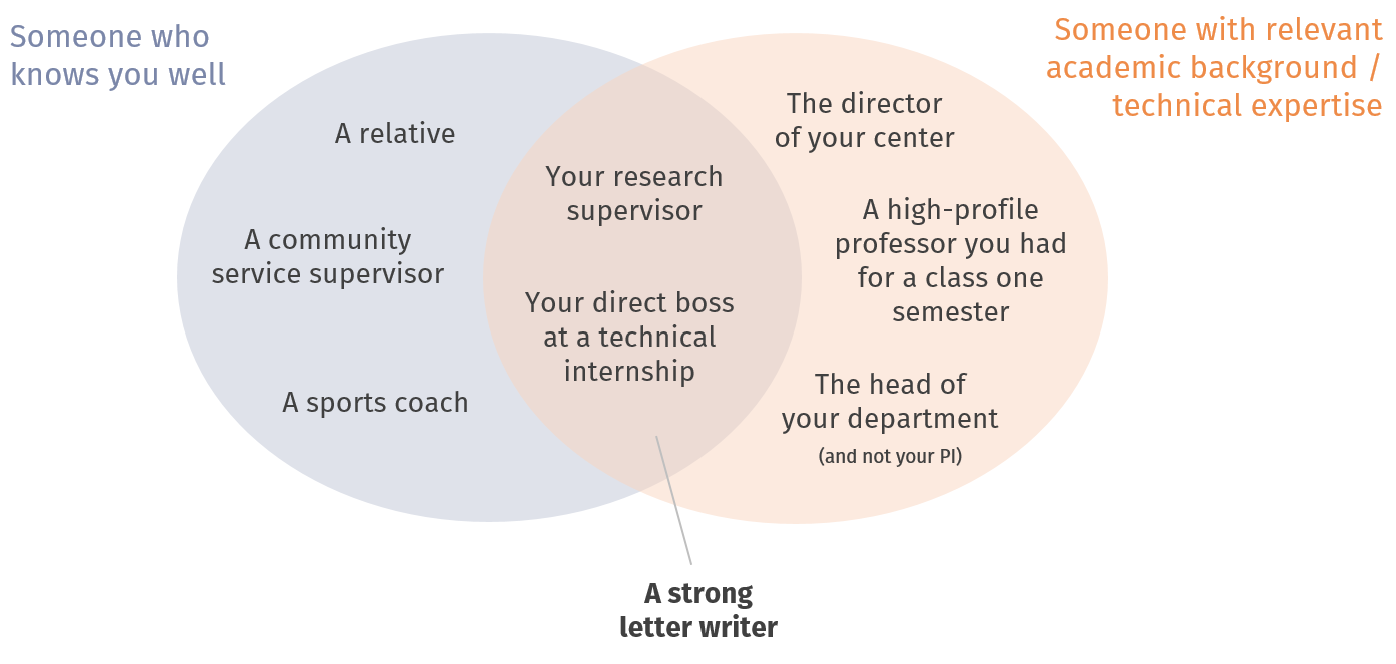

“An effective letter isn’t one that’s positive—it’s one that’s specific,” said one professor. When looking for a letter writer, you want a combination of someone who knows you well and who also demonstrates the technical skills that you want them to highlight to support your application. They should be people you have “worked closely and successfully with” and who will be able to share “personal details and insights gleaned from direct experience” with you.

Do not hesitate to ask faculty (without asking for specifics) if they are in a position to write you a strong letter of recommendation. If they can’t, thank them and ask someone else. They might even tell you that they don’t feel confident serving as a reference for you, so consider having backups.

3. Help your mentors

Give them time, 3-4 weeks for most jobs and programs (one month is “ideal”), and 6-8 weeks for faculty applications. Anything less than 2 weeks is inappropriate. Faculty are busy and will need the flexibility to schedule the writing task itself as well as the time to do their own research about your target job or program. If they know the person you’re hoping to work with, they can better customize their letter and establish a stronger match.

Give them information, from logistical details to your long-term aspirations. If you can, provide all the information at once rather than little bits at a time, and keep it organized.

| Logistics |

|

| Performance |

|

| Personal information |

|

Most fundamentally, it’s best to “cultivate a relationship with the recommender; the better they know you, the better the letter.” This is hopefully something you started doing long before you requested a letter.

Do not draft the letter on behalf of your references! Though this may be a common practice in some fields or with some professors, none of the faculty we connected with wanted their students to send a draft. In fact, several expressed their “strong dislike” toward that idea:

- “Leave it up to the recommender to decide what to include, though you may point to specific experiences that you’d like to see highlighted.”

- “It is – in my opinion – a bad idea for the student to tell the faculty what to write. The faculty member puts his/her name on the letter and has complete authority to write whatever he/she sees fit.”

- “I don’t appreciate being told what to write. It should really be an assessment free from outside influence.”

You should not provide a list of talking points (it’s “off putting”) but you can point to specific experiences or projects worth mentioning. One professor wrote, “students should direct me to the aspects of their curriculum/CV that they think are more relevant to the position. Also, adding something personal that can be leveraged (not copied) is also useful, so that the letter looks more personal.” Mostly, stick with the information listed in the table shown above.

If you’re an undergraduate student who worked more closely with a senior graduate student or postdoc, you can let the PI know that they may contact the student/post-doc mentor for additional information. Do not solicit a blurb from your student/postdoc mentor and forward it directly to your PI. Let the PI decide whether or not to reach out.

4. Follow up

Send a reminder one week before the letter is due and, if needed, the day before. Students “should be empowered to remind me frequently until the letter is submitted,” wrote one professor, though others admitted that five or more reminders would be “annoying.” If you’re not sure, simply ask your mentor when and how often to check back in with them. Communication is key!

When the time comes, share your application results with your references along with a thank-you note. This is purely a suggestion from the Comm Lab, given how invested the letter writers are in your success! Your mentors spend between 45 minutes and 5 hours on each letter, which includes the amount of time they need to actually write the letter and the time they spend doing their research (reviewing your information, understanding you on a holistic level, looking up your target institutions and the people who might serve on those review committees, etc.). “This is a lot of time and effort,” wrote one professor, “but the reason each letter takes me so long is that I try hard to do a good job of them :-)”

Published October 2, 2020

Related articles:

- “Tells Us About a Time When”: The Key to Strong Letters of Recommendation

- CV/Resume

- Graduate School Personal Statement

- Fellowship Personal Statements

For customized feedback at any point in your application process, schedule a time to speak with a Communication Fellow.