NOTE: As of September 2024, the structure and requirements of 22.911 have changed. The article below has not been updated to reflect the new course content, although many of the guiding principles still apply. Edits are in progress on this page.

Congratulations! You’ve submitted your thesis prospectus, which officially makes you a doctoral candidate. Now you’ll be enrolling in 22.911 (Doctoral Seminar in NSE) every year until you graduate. Being in 22.911 means attending a dozen seminars by your peers and, at some point, giving your own 20-min research presentation.

Whether it’s your first time in the course or your fourth time, how you practice communication will depend on your strengths and priorities. You also have access to plenty of resources: the Comm Lab, your advisor and lab mates, written and live feedback from the audience, and a video recording of your talk. Ultimately, what you gain in 22.911 is based on what effort you put in.

Below are a few pointers and exercises to help you make the most out of your seminar experience as a presenter, a host, and an attendee.

| Contents |

| 1. As a Presenter 1.1. Properly plan your talk 1.2. Write an effective abstract 1.3. Set goals and track your progress 1.4. Manage the feedback you receive 2. As a Host 2.1. Before the talk 2.2. The day of the talk 3. As an Attendee 3.1. Give effective feedback 3.2. Draw inspiration from the talk 4. Activity Handouts |

1. As a Presenter

As a presenter, you get to not only practice giving an effective research talk but also receive input from peers inside and outside of your research group.

1.1. Properly plan your talk

Always start by asking these strategic questions: “who,” “why,” and “what.” On the right is a handout to help you prepare. Do this even if you intend to recycle an old presentation. In fact, do this especially if you’re planning to recycle an old presentation! This way, you won’t end up with bits and pieces being thrown together somewhat haphazardly.

Always start by asking these strategic questions: “who,” “why,” and “what.” On the right is a handout to help you prepare. Do this even if you intend to recycle an old presentation. In fact, do this especially if you’re planning to recycle an old presentation! This way, you won’t end up with bits and pieces being thrown together somewhat haphazardly.

You can read more on how to structure a slide presentation. Here are key things to consider:

- WHO is your target audience? In 22.911, this would be an NSE graduate student who has passed quals, i.e. someone who has taken the modules but who isn’t necessarily familiar with your research area. Knowing this, you can gauge the right amount of background versus technical detail to include.

- WHY are you giving this talk (other than you “have to”)? What are your objectives for your audience and for yourself? You may be looking for feedback on your new research direction, testing a data visualization idea before an upcoming conference talk, or hoping to get your peers really excited about your work. Or you might just want to practice being a more confident public speaker.

- WHAT is the one thing you want your audience to take away from your talk? You should be able to identify this core message in one sentence (ex: “My method allows us to run more accurate simulations” or “We’ve discovered something important that can impact your work”). Once you’ve clarified your message, you’ll be better positioned to decide what content to include and what to exclude. Think of it as “more signal, less noise.” (The metaphor of “signal-to-noise ratio” comes from Jean-luc Doumont’s book Trees, Maps, and Theorems.)

Only after being clear on these three questions should you proceed with “how.”

HOW you put everything together involves a wide spectrum of considerations, including your content organization, logical flow, slide and figure design, use of animations, vocal delivery, body language, and more. Depending on your objectives and strengths as a presenter, you may dedicate more time to one area than others—though hopefully, you will never sacrifice structure in favor of slide design!

1.2. Write an effective abstract

The abstract is your first opportunity to get the audience excited about your talk, so take the time to review how to write an effective one or use the handout provided here. Whether you choose to start with some motivating background or jump in with the takeaway message, be sure to include key results and the significance of your work. Do not end with, “results will be discussed.” (As an NSE professor pointed out, it’s like going to a restaurant and being told that “food will be served.”)

The abstract is your first opportunity to get the audience excited about your talk, so take the time to review how to write an effective one or use the handout provided here. Whether you choose to start with some motivating background or jump in with the takeaway message, be sure to include key results and the significance of your work. Do not end with, “results will be discussed.” (As an NSE professor pointed out, it’s like going to a restaurant and being told that “food will be served.”)

1.3. Set goals and track your progress

The hope is that everyone becomes a more effective and more confident presenter as time goes on, but we also acknowledge the following:

- If you’re a returning 22.911 student, it’s now been a year since your last seminar, and it’s hard to remember how things went.

- You may not care to give the most outstanding talk of the year. You might even just aim for “good enough.”

Regardless of how ambitious you’re feeling, be deliberate about tracking your progress. Identify 2-3 communication goals before your talk, considering both the product (the presentation itself) and the process (designing, creating, revising, not waiting till the last minute…). You can review feedback from previous years or simply pick new metrics to focus on. Here’s a handout to help you with your self-assessment.

Regardless of how ambitious you’re feeling, be deliberate about tracking your progress. Identify 2-3 communication goals before your talk, considering both the product (the presentation itself) and the process (designing, creating, revising, not waiting till the last minute…). You can review feedback from previous years or simply pick new metrics to focus on. Here’s a handout to help you with your self-assessment.

1.4. Manage the feedback you receive

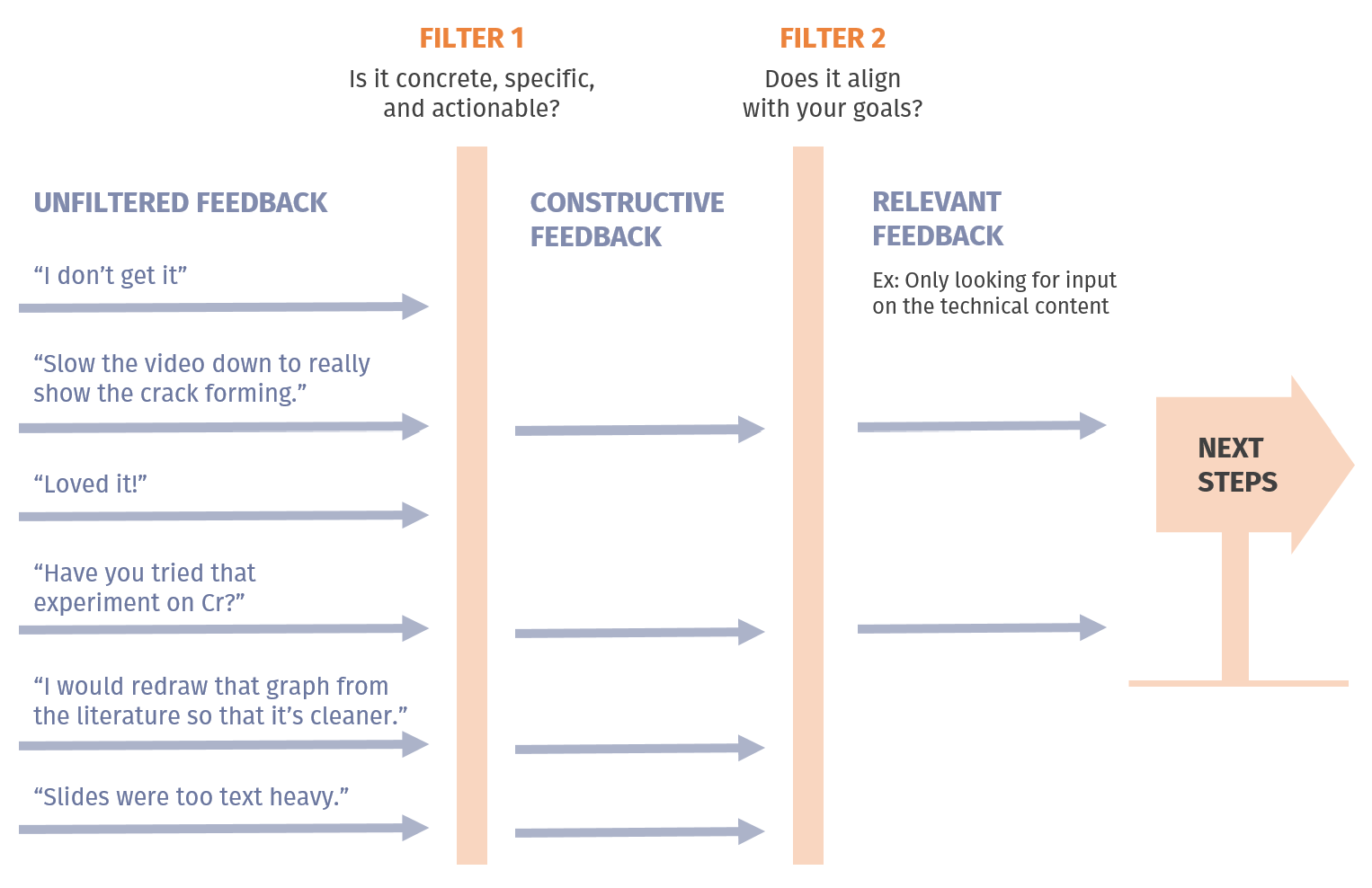

After your talk, you will be receiving technical and communication-related feedback, in written and verbal forms. In all cases, you can apply strategic filters to decide which comments to consider and implement.

Filter 1 helps you eliminate feedback that fails to be concrete, specific, and actionable. This is mentally helpful when you go through the attendees’ written feedback, which is a one-way, anonymous transaction. If you receive vague feedback during the live session, you should ask for clarification.

- Examples of unhelpful feedback: “I don’t get it,” “I don’t believe your results,” “nice job.”

- Examples of helpful feedback: “I’m not convinced that your data is statistically significant. Could you add error bars next time?” “The labels on slide #17 were too small to read from the back,” “I liked your graphical summary at the end. It was helpful to see everything in one place.”

Filter 2 is for you to prioritize feedback that aligns with your goals. For instance, if your main objective is to seek technical input from those outside your area, you can attach less importance to comments about slide design (unless your design gets in the way of your main goal). You can apply Filter 2 before you launch into your talk, or before the live feedback session.

- Filter 2 examples: “This talk is actually for an ANS conference I’m giving next week, so I’m open to all of your feedback.” Or “I know my slides are a bit bare, but where I would most appreciate your input is the methodology.”

Here’s a caveat about Filter 2. Filtering out feedback that’s not relevant is different from discarding feedback that you “don’t like.” You might also receive unsolicited feedback that reveals important elements you hadn’t considered but really should look into. So make sure you recognize if/when decisions are emotionally driven and whether they make sense for your needs, broader goals, and bandwidth. If you feel overwhelmed, take a few days to regain your footing and/or reflect with a supportive colleague.

Receiving feedback is hard and can be stressful. Still, you hold more power than you might think!

2. As a Host

As a host, you’ll be introducing the speaker, keeping time, and moderating the discussion that follows.

2.1. Before the talk

Three to five days before the talk, contact the speaker so you can begin preparing the introduction. Collect their basic background information, clarify any pronunciation concerns, and ask for a major takeaway of their talk. To ensure you are comfortable in this role, practice the introduction a few times prior to their talk.

2.2. The day of the talk

Arrive a few minutes early and plan for the following:

- Before the presentation begins, remind the speaker and the audience of the format. Make sure the speaker knows your time signals, and encourage the audience to provide concrete, specific, and actionable feedback in their written evaluations.

- During the talk, start thinking about a couple of technical questions and communication-related observations ahead of the Q&A. Give the speaker a visual cue when they have 5 minutes and 1 minute remaining.

- After the formal presentation, open the floor for technical questions. If the audience seems hesitant at first, offer your own question to get the conversation started. If the Q&A becomes a series of back-and-forths between the presenter and a single attendee, you may invite them to continue the conversation after the formal session.

After about 10 minutes (may be longer in some 22.911 sections), open the floor for communication-based feedback by inviting the presenter to speak first. Ask them if there is any specific kind of feedback they are most interested to hear. Again, offer your own comments if the room is quiet at first.

Keep an eye on the time for the total session, if things are going long, politely request that any additional discussion be continued offline. Thank the speaker for the seminar, and hand things off to the next moderator if appropriate.

3. As an Attendee

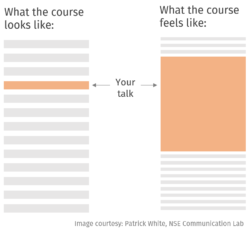

In 22.911, it can feel like you’re “on” when you’re presenting and “off” when you’re not. While there is less pressure on you to perform well as an attendee, try paying attention to two things: how to help the presenter in front of you, and how to help the presenter in you.

In 22.911, it can feel like you’re “on” when you’re presenting and “off” when you’re not. While there is less pressure on you to perform well as an attendee, try paying attention to two things: how to help the presenter in front of you, and how to help the presenter in you.

3.1. Give effective feedback

Helpful feedback isn’t just an opinion; it is usable information. Whether it is technical or communication-related, your feedback can come in the form of a question (“Have you considered… ?”) or an observation about your own reaction (“I got confused about…”). Here are some additional considerations:

When asking a question, make sure you understand what you’re asking of the presenter. Are you asking them to speculate? Elaborate? Explain? Describe? Clarify? Estimate? Illustrate? Expand on something? This would help to avoid questions that don’t resemble questions.

When providing comments, make sure that they are:

- Concrete, by including tangible information. Ex: “It seemed like you jumped right into the experiment, and I wasn’t sure I understood the motivation.” (Not concrete, unhelpful: “You need a better intro”)

- Specific, by pointing to something in particular. Ex: “Doing a flow chart instead of a traditional outline slide was very helpful. I was able to see the logic between each part.” (Not specific, unhelpful: “Nice talk!”)

- Actionable, by considering what the presenter could do in response. Ex: “I would slow down the movie a bit so we can see exactly when the crack started forming.” (Not actionable, unhelpful: “That reminds me of this other loosely-related phenomenon.”)

The practice of giving and receiving feedback is a collaborative effort. When carried out well, it’s a learning opportunity for everyone involved. You can also review NSE’s community standards in your 22.911 syllabus.

3.2. Draw inspiration from the talk

We learn best by doing, but we can learn quite a bit by paying attention too! As an attendee, you can actively appreciate whether something is working or not (animations, white text on dark background, use of a laser pointer) and take notes for yourself. Especially if your talk is coming up soon, you may be inspired by the energy of today’s speaker or be reminded to not end your presentation with a “Thank you!!!” slide.

You can also learn a lot by listening to the live feedback session. For instance, you may realize that others were also confused by that graph on slide #9, and someone in the audience might have a neat idea on how to improve it. Engaging in active listening will ultimately help you grow as a presenter, and get more value out of your 22.911 experience.

4. Activity handouts

Throughout this article, we recommended that you go through a number of activities. You can find them all here.

To get started or receive feedback on your seminar talk, make an appointment with us. We’d love to help!