The goal of a paper is to prove that you did or found something new, and the Results section is the evidence supporting this new conclusion. The Results section connects your Methods to your Discussion. A great results section maximizes the clarity and understanding of your data. The data is organized into a logical fact pattern that builds to a conclusion, so one outlining strategy is to start from your conclusion and walk backwards to form a cohesive narrative.

1. Stop and collect your thoughts

Often, people write by stream of consciousness: before they know where they want to go they just start writing. The outcome is a document that is hard to read for anyone but the writer. Plan before you write.

1.1. What is your assertion?

The Results section is the roadmap to your assertion. Focus on the purpose:

- Describe your data in a narrative as objectively as possible

- Provide evidence for your take-home message

The Results section offers support for interpreting data by explaining experimental logic, highlighting important data features, and stating your conclusions. Only introduce some analysis in the results section if it makes more logical sense in the organization of your paper, but most of the interpretation should be in the Discussion section (unless you deliberately combine your Results and Discussion sections).

1.2. Are your readers experts in your field?

Tailor your writing to the audience. Non-experts will benefit the most from your explanations in the Results section. Do not assume that readers know what the purpose of a method is or that the meaning of an observation is self-evident. State your motivations and interpretations as explicitly as possible. Experts in your field may draw their own conclusions from your data, but help readers who don’t feel confident analyzing your data and conclusions based on figures alone.

2. Organize, outline, and go

You’re almost at the writing stage. Now that you have clarified your assertion and audience, figure out the connection between your results before filling in the details.

2.1. Outline the fact pattern to match the figures

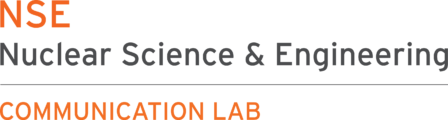

Organize your data and conclusions into a logical flow to create a cohesive narrative. Here are two ways to do this:

2.2. Show minimal essential data

Identify the minimally essential information to avoid distraction and maximize the clarity of your writing. Consider what is obvious and what needs elaboration, and focus only on what is necessary for logical completeness.

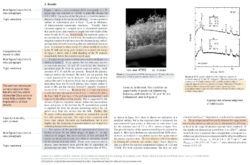

Do not include data that is irrelevant to the given conclusion. Selecting relevant data can be a judgement call and also depends on journal article length restrictions—the shorter your article, the more content you might have to move to Supplementary Information, or leave out. Here are tips on what to include:

Correlate the amount of text and the importance of a result to the paper’s main conclusion. It’s tempting to write more when describing a result that’s complicated or confusing, but don’t fill your reader’s head with distracting details. As you write, keep reminding yourself what the most important conclusions are, and allocate the most space and detail for their supporting details.

2.3. Fill in the details and work on the transitions

Each paragraph corresponds to a unique experiment (or a group of closely related experiments) or a single figure or subpanel within a larger figure. Make sure to smoothly transition from one result to the next.

- Start each paragraph with a topic sentence that describes the takeaway result from that experiment. Your topic sentence can also explain the rationale for the experiment (ex: “In order to determine X, Y was performed, showing Z results”).

- Then, describe your data and the conclusions that you learned from it. Do so in a logical order, such as pro then con, most to least important, and experimental versus simulation results.

- Conclude with a transition sentence that sums up findings, and, if necessary, justifies why you moved to the next experiment or hypothesis.

The only time that speculation can be included in Results is when it is necessary to explain a transition between experiments. Ex: “Having observed data A, we speculated that mechanism B might cause phenomenon C. Hence, the next experiment tested the activity of mechanism B by…”

3. Quick tips

- Ask a friend from a different lab to read your Results to identify unexplained jargon or gaps in your rationale.

- Results should be written in a tense consistent with the rest of your paper.

- Be as objective as possible. Avoid phrases like “interestingly, we found that…”, unless that “interestingness” can be concretely justified (ex: the result contradicts a major hypothesis, or past findings in the field).

4. Annotated examples

To get started or receive feedback on your draft, make an appointment with us. We’d love to help!