The Methods section serves two purposes: explain the choices you made in your experimental design, and provide sufficient detail for other informed scientists to reproduce the experiments. Although the length and depth vary among journals and publishers, it should be written in a clear and direct way—whether it is in the active or passive voice.

| Contents |

| 1. Before your start 1.1. Identify your purpose 1.2. Analyze your audience 2. Writing your methods 2.1. Why this methodology? 2.2. Only provide essential details 2.3. Active versus passive voice 3. Quick tips 4. Annotated examples |

1. Before you start

1.1. Identify your purpose

The purpose of a Methods section is to describe how the knowledge gap posed in the Introduction was answered in the Results section. Not all readers will be interested in this information. For those who are, the Methods section will help readers:

- judge whether the results and conclusions of the study are valid. The interpretation of your results depends on the methods you used to obtain them. A skeptical reader will read your Methods section to see if your results can be trusted, so you need to show that you chose the most appropriate methods and performed the necessary controls.

- repeat the study. For readers interested in replicating your study, the Methods section should provide enough information for them to obtain the same or similar results.

1.2. Analyze your audience

Typically, only readers in your field will have the knowledge to assess your methodology or want to replicate your study. Most audiences are more likely to skim through the Methods section and proceed straight to the Results. You can therefore assume that people reading your Methods understand methodologies that are frequently used in your field. Look at articles previously published in your target journal to gauge the appropriate level of detail.

If your paper is designed to appeal to experts in more than one field, you still need to write your Methods for a single set of experts. For example, say you developed a new algorithm for calculating the viability of nuclear reactors in different types of electricity markets. Is your goal to show economists how they can be involved with the nuclear industry, or to show nuclear engineers how to use your algorithm to assess reactor design? In each case, assume the appropriate level of expertise in the two fields and provide more in-depth explanations of the areas where your target audience will be weakest.

2. Writing your methods

2.1. Why this methodology?

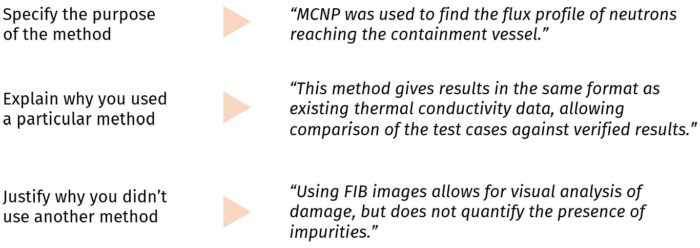

Describe why you chose this specific methodology so the informed reader can assess your experimental design (and the reliability of your results). For example, you don’t need to explain how MCNP works, but you may need to explain why it is the appropriate analysis code for the data you are trying to create (and possibly why you didn’t choose another method).

See other examples here.

2.2. Only provide essential details

Provide enough information for those in the field to reproduce your experiment and reach the same conclusions as you do in your paper.

Papers for standard methods can be cited, but any modifications or alterations must be clearly stated. Likewise, specify any factor that might change the conclusions in your paper. When citing methods, cite the original paper in which a method was described instead of a paper that used the method. This helps avoid chains of citations that your reader must follow to find information about the method.

2.3. Active or passive voice

Your Methods should be written in the past tense to describe what you did, but whether you should use the active or passive voice is often a point of debate.

The passive voice (such as, “The model was developed to represent…”) is considered to be objective and impersonal, and well-suited to science writing. Although the passive voice has been dominant for many years in scientific writing, the active voice (such as, “We developed the model to represent…”) is becoming much more common. The active voice will also be used when the subject isn’t the experimenter. Ex: “Core turbulence measured with a reflectometer at r/a = 0.55, showed reduced fluctuations across the L-I transition.” (Source: White, A.E., et al. Physics of Plasmas 22, 056109, 2015).

Be aware of the style of your target journal, and of the preferences of your advisor or group. For example, Nature encourages the use of the active voice with first-person pronouns. According to its guide on How to write a scientific paper, “experience has shown that readers find concepts and results to be conveyed more clearly if written directly.”

3. Quick tips

- You may choose to include informative figures to help describe your experimental set up. Head over to Figure Design to learn more.

- Consider using subheadings to organize your Methods section. Group related experiments and establish a logical flow. The subheadings in your Methods don’t have to strictly dictate the subheadings in your Results section.

4. Annotated examples

To get started or receive feedback on your draft, make an appointment with us. We’d love to help!