Whether the personal statement is called Career Goals, Intellectual Excitement, or Statement of Purpose, it should contain a coherent theme that ties together your experiences, the goals of the program, and your research interests. Regardless of the structure you choose, the committee reading your application should get to know your scientific identity and see a place for you in their program.

Check out NSE’s page on fellowships to see which ones you may be eligible for. For more information on international fellowships, contact the Office of Graduate Education.

1. Before you start

Most applications are rejected if they look generic or the applicant appears uninformed about the target program. Your strategic goal is to demonstrate that you understand what they are about, and that your qualifications, values, and interests are a match for them. So don’t start writing yet—not until you’ve clarified this match for yourself.

1.1. Who are you?

You are more than a research project. Spend some time reflecting on your experiences and values. What do you care about? Why do you need this fellowship to accomplish your ulterior objectives?

Think beyond the technical space as well. If you only have one summer research internship because you spent your summers mentoring under-served high school students, use that to demonstrate your commitment to service and diversity. If you discovered a passion for fusion energy in your senior year and all your previous experience was optimized for an industry job, show that excitement to the committee. Whether it’s growing up on a farm, hiking the Appalachian Trail, or leading a high school robotics team, these experiences can be used to demonstrate motivation, commitment, and a good work ethic. These are attributes that can help you be successful in research.

1.2. What is your target program?

Take the time to carefully read about the program. Consider the goals of a fellowship and pay attention to any special requirements (e.g. Broader Impacts and Intellectual Merit for NSF applications) as well as any tips they might offer on their websites.

As for the backgrounds of the actual reviewers, the evaluating committee may vary from non-technical readers to specialists in your scientific niche. Usually, they are academics from your broad area of science (e.g., nuclear engineering) but not from your specific area (e.g., thermal hydraulics). Consider this as you choose the details and vocabulary to describe your current and former research and activities.

2. What goes in your statement

As long as you stay within the specifications set by your target program, you have the freedom to structure your personal statement as you wish. Some programs have specific prompts seeking 300–500-word answers, and others ask for 2–3-page statements.

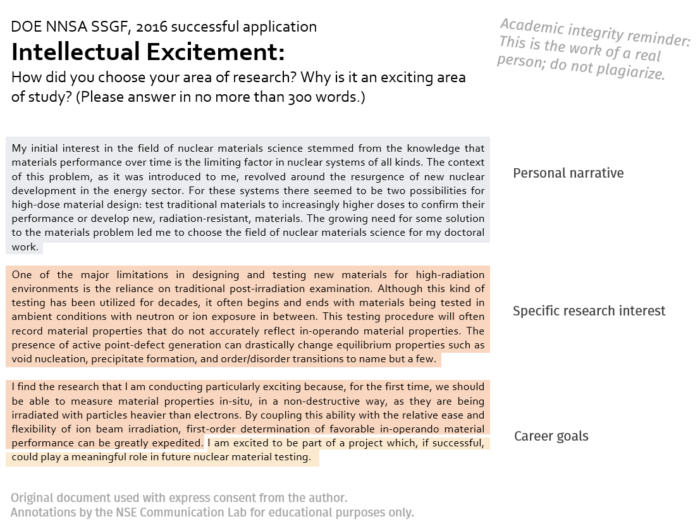

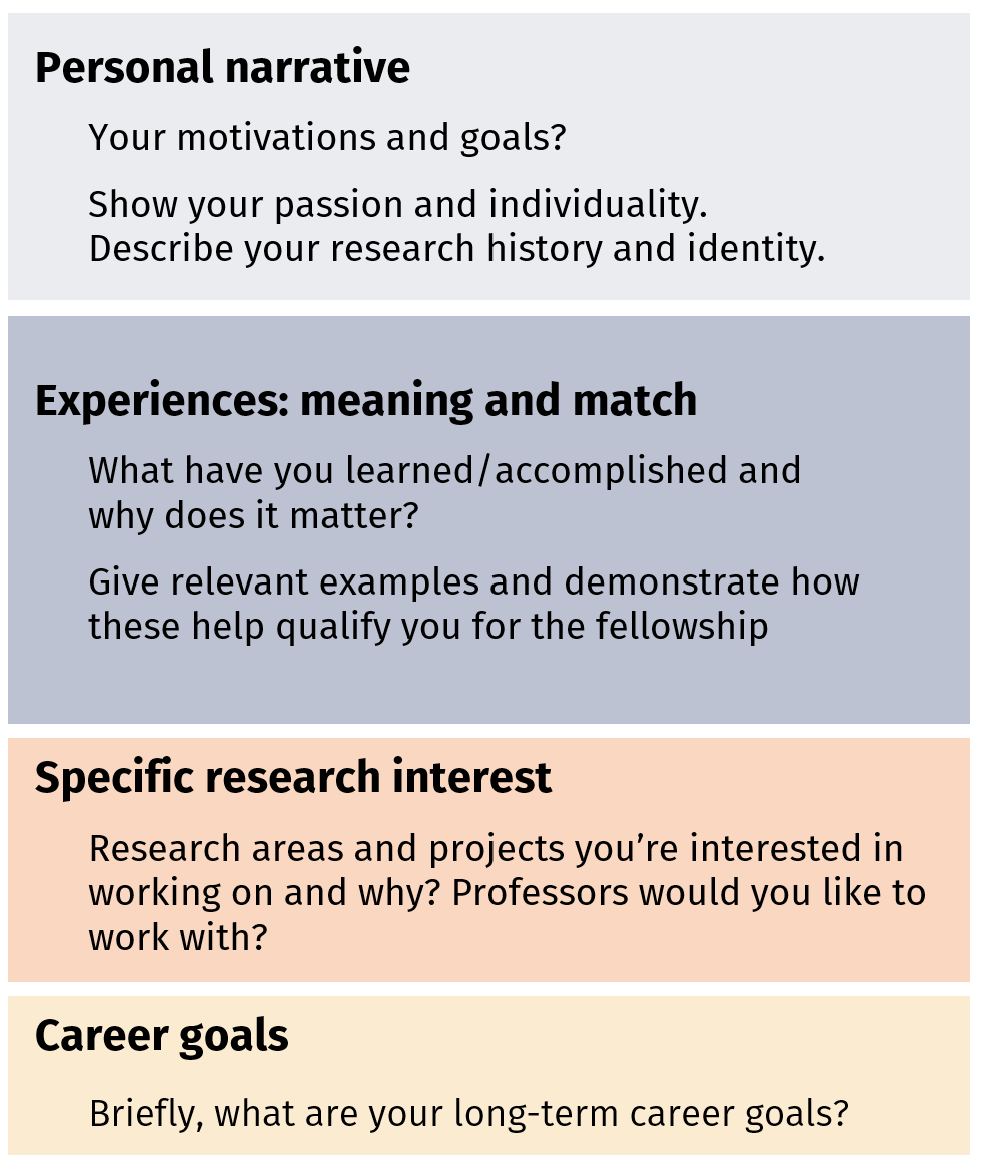

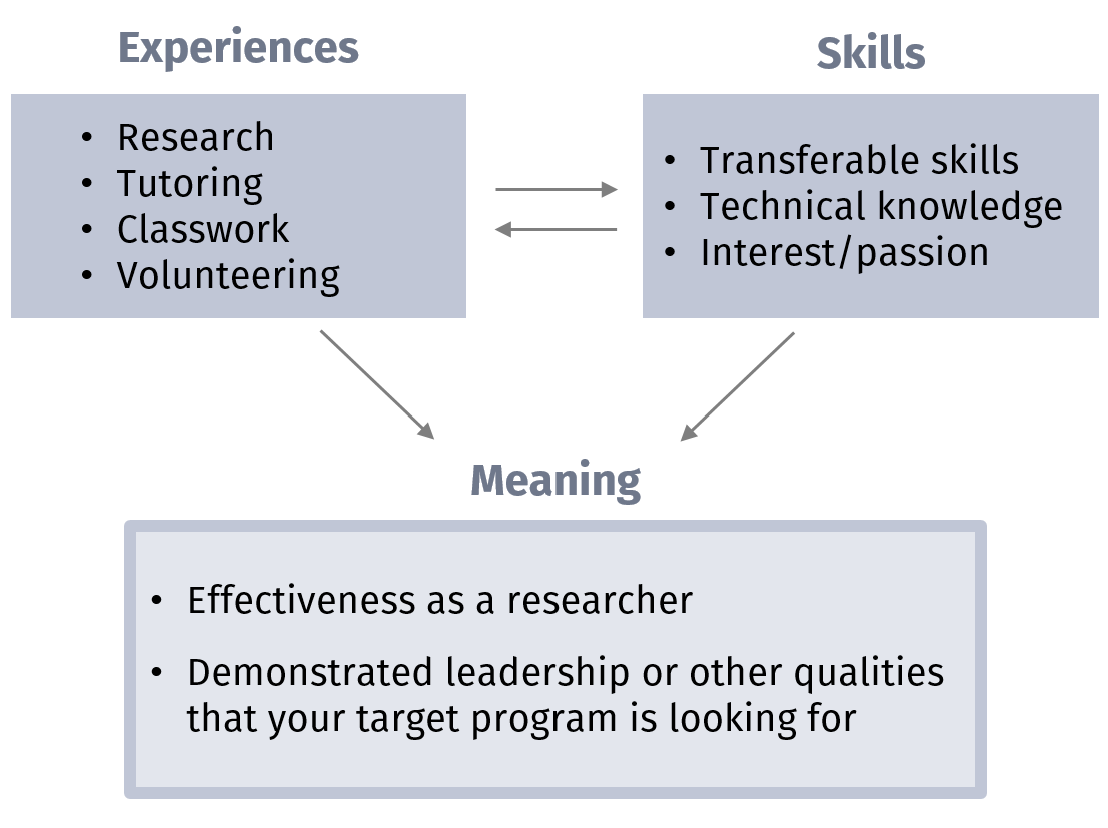

For those longer statements, be sure to include some sort of personal narrative, relevant experiences to back up this narrative, specific motivation/research interests, and career goals (see figure). These don’t have to be unique sections in this specific order, as shown in our examples.

For those longer statements, be sure to include some sort of personal narrative, relevant experiences to back up this narrative, specific motivation/research interests, and career goals (see figure). These don’t have to be unique sections in this specific order, as shown in our examples.

2.1. A personal narrative

Build a personal narrative that ties together your personal history, experiences, and motivations. In addition to a few paragraphs (2–3) at the beginning of your statement, you can weave your motivation and goals throughout your document to create a cohesive story. This cements your identity into the minds of the reviewer. If they remember you, they will be more likely to accept you!

2.2. Your experiences: meaning and match

This section is typically 3–6 paragraphs long, with a few examples to illustrate your point. To decide which experiences to share, ask yourself these two questions:

1. In which ways did this experience help me grow?

One common mistake is to describe an experience in great detail and fail to translate it into skills or qualifications. Instead, explicitly say what that experience means for your future goals. Ex: Building a fusor in high school has prepared you for laboratory work, or volunteering with a recycling program shows your dedication to protecting the environment. More details here.

2. Why should the review committee care?

Make it very clear that you are a match for their program. Tie your experiences and their meaning directly to the qualities that the fellowship program is looking for in successful applicants. For NSF GRFP applications, you’ll need to have explicit sections for Broader Impacts and Intellectual Merit. Be sure to explain how you and your project will fulfill these two goals.

2.3. Research interest

Spend 1-2 paragraphs describing your research goals. Depending on the application, you may or may not have a specific research statement. If you have a separate research statement, save the more specific research topics for that document, and reference them in your personal statement. If there’s no research statement, you should briefly summarize the projects you want to work on, and how those fit in with your experiences.

2.4. Career goals

Wrap up by looking into the future. Your long-term career goals should be a logical completion of the personal narrative you’ve built throughout the document, and usually takes up one paragraph. Will you leverage the fellowship to explore new and impactful ideas without established funding? Will you be able to engage in public outreach and education more easily with a secure source of funding? Answering these questions will show that you are forward-thinking and will put the fellowship to good use.

3. Maximize effectiveness

Now that you’ve got the main pieces down, revise your document to maximize its impact.

3.1. Be specific and quantitative (show, don’t tell)

Make your relevant experiences tangible by stating specific outcomes such as awards, discoveries, and publications. Whenever possible, try to quantify the experience. How many people were on your team? How many protocols did you develop? As a TA, how often did you meet with your students? Here are some examples of vague and concrete experiences:

| Vague experience (“Tell”) – less effective |

Concrete experience (“Show”) – more effective |

| My mind was opened to the possibility of using different programming languages together to create code that is faster to run and easier to understand and modify. | During this project, I collaborated with other group members to develop a user-friendly Python wrapper for a 10,000-line Fortran library. |

| I won the physics department’s Laser Focus prize. | I won the physics department’s prize for the top student in my cohort of 20 students. |

| I learned about how particle accelerators work. | I took apart and repaired two electromagnetic steering filters inside of a particle accelerator. |

3.2. Explain the meaning of your experiences

Your goal in sharing your experiences is to demonstrate that you have the qualifications, qualities, and promise found in successful recipients of that specific fellowship. Therefore, you will need to not only choose experiences wisely but also state specifically what they mean within the context of your application.

Here are some example experiences that have been expanded to contain meaning:

Here are some example experiences that have been expanded to contain meaning:

| Experience only (less effective) |

Experience and Meaning (more effective) |

| “As a senior, I received an A in a graduate-level CFD course.” | “My advanced coursework demonstrates my ability to thrive in a challenging academic environment. A graduate-level computational fluid dynamics course challenged me to…” |

| “I independently developed a digital data acquisition software for gamma spectroscopy.” | “My research experiences have developed my problem-solving abilities. When the commercial software was insufficient for my gamma spectroscopy project, I … This has given me the confidence and software skills to attack open-ended research problems.” |

3.3. Match your level of specificity to your current academic level

Your current education level should influence the tone and topics you address in your statement. For instance, the NSF GRFP accepts applications from three levels of students: senior undergraduates, first-year graduate students, and second-year graduate students. The tone and specificity of your application should reflect your level. While senior undergrads can write generally about their future goals, second-year graduate students should write about specific progress towards career goals.

3.4. Try section headers

Consider labeling your sections to show the structure of your statement. These will guide the reviewer through your document and explicitly call attention to sections where you answer questions from the application material. In an NSF research proposal, “Intellectual Merit” and “Broader Impacts” section headers are specifically requested.

4. Quick tips

- Start early. It is critical that you spend the time to carefully read through the program’s solicitation and guidelines, and that you have the chance to receive and incorporate feedback on your drafts. The evaluation committee will be reviewing hundreds of applications and yours will be quickly dismissed if it doesn’t quickly make an impact.

- Pay close attention to formatting instructions. The NSF GRF Program is notorious for rejecting applicants who use the wrong font size or line spacing. Whatever fellowship program you apply to, make sure to follow the formatting instructions.

- Read the prompt carefully. Each fellowship is unique and will have unique requirements for their applications. If anything in those requirements contradicts with advice you read here or elsewhere, go with the application guidelines.

- Double-check your spelling and grammar. A well-written statement demonstrates your communication skills, which are essential for success as a researcher.

- Be strategic with letters of references. Do not go to professors who you think will write you the most positive letters. Instead, go to those who can write about specific experiences that demonstrates the skills that you want to highlight in your application. Each letter should bring new and complementing insights into who you are as a student and researcher.

- Check out other fellowship resources, especially those on the MIT Office of Graduate Education website. If you are an international student enrolled at MIT, you can email OGE (oge@mit.edu) to learn more about your options.

5. Authentic Examples

Selection criteria can vary from year to year. Be sure to follow the most up-to-date guidelines provided by your target fellowship program, especially if you are referencing older examples. You can also find examples from across different disciplines here (scroll to the bottom).

To get started or receive feedback on your fellowship personal statement, make an appointment with one of us. We would love to help you!