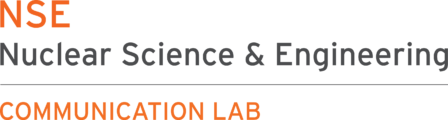

Criteria for Success

- The presentation starts with the larger motivation for the work shown.

- The research shown in the slideshow concretely connects to the larger motivation.

- Experiments and their results are connected to the larger motivation.

- Each slide tells a message.

- Each slide gives no more information than is required to support the message.

- The title text stands on its own, and most other text supports the visuals.

- The audience will take away the messages that achieve the presenter’s goals.

Structure Diagram

Identify your Purpose

Know your own goals as a presenter, and structure your presentation based on your goals. This will make it easier for your audience to follow your logic and identify the most important points when providing feedback.

For example, if your goal is to get feedback from your colleagues on an experimental strategy, focus more on the experimental methods. Compare the advantages and disadvantages to alternatives. Explain why you think your proposed experimental design will give more useful results than other experimental designs would.

By contrast, if your goal is to communicate a new scientific result, then you should focus on the results and broader implications rather than your methodology. Avoid talking about specific methods (e.g., say “I measured magnetic properties of superconducting materials” rather than “I used vibrating sample magnetometry to obtain hysteresis curves for rare-earth barium-copper-oxide superconductors”). Say how your findings impact the broader motivation.

In less formal settings, like a lab meeting, you can explicitly tell your audience what you’re looking for (e.g., “I’d appreciate critique of my experimental methods”).

Analyze your Audience

Different audiences pay attention to different things. Engineers are interested in innovations, scientists are interested in broader scientific questions, and venture capitalists want to hear about the money. Your presentation should speak to and excite your audience.

That being said, you probably know the subject material in your talk better than anyone, so what feels to you like a natural starting point for your presentation could easily feel baffling to others. Your presentation should start with something that everybody cares about and move step by step toward what you actually did and why. This may seem like a waste. However, if you spend too much time on background material, you only waste a few minutes. If you spend too little time on background, your audience might not understand your work and the entire talk will be a waste.

Another way to help your audience understand you is to avoid jargon, keeping in mind that the same words or images can be “useful detail” to one audience but “jargon” to another.

Skills

Connect your work back to broader motivations and hypotheses

At the beginning of your talk, develop the broad context for your work and then lay out the motivating questions you aim to answer. The audience should understand how the answers to those questions will impact the broader context.

When showing data, be clear about what that data has to say about those motivating questions. What do different experimental outcomes mean for those larger questions?

Transitions between parts of the talk should also reference the larger motivating questions. A weak transition like “After imaging this sample, I decided to also use X-ray diffractometry” doesn’t help orient the audience. A stronger version might be, “Imaging with scanning electron microscopy and electron backscatter diffraction showed us that zirconia was present, but the crystal structure was not clear. We then performed X-ray diffractometry to determine if the zirconia presented with a monoclinic, tetragonal or cubic crystal structure.” A slower, more deliberate transition will give your audience time to process what they just saw and figure out how to connect that information with the rest of your talk.

“Introduce” your data

Make sure your audience will be able to understand your data before you show it. They should know what the axes will be, what each point in the plot represents, and what pattern or signal they’re looking for. If you’re showing a common type of plot to an audience that’s familiar with that kind of plot (e.g., a FACS plot for immunologists or a gene circuit diagram for synthetic biologists), there’s no need to worry. But if you show the data before the audience knows how to read it, then they’ll stop listening to you and instead scrutinize the figure, hoping that a knitted brow will help them understand.

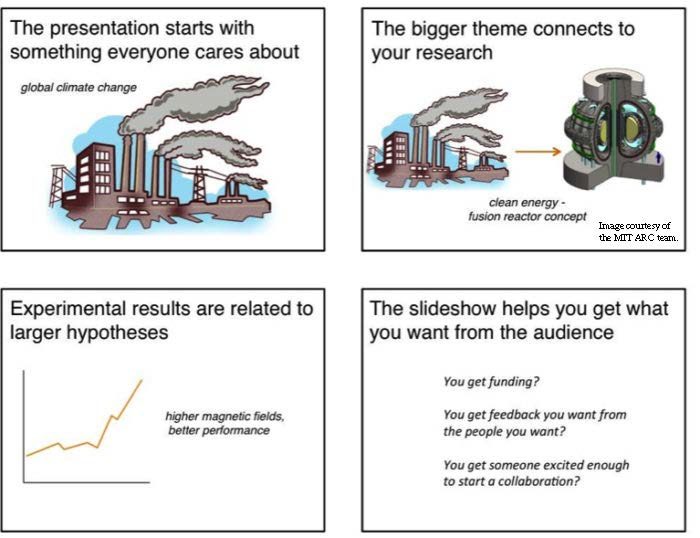

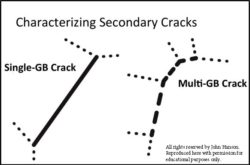

If you are worried your audience won’t understand your data, one approach to try is to show cartoons of what the resulting data would look like if your hypothesis is true and what the data will look like if the hypothesis is false. Show the real data afterward.

Try visually explaining unfamiliar data. For an audience unfamiliar with SEM/EBSD imaging of grain boundary cracks, the presenter first shows a slide explaining how single-grain boundary cracks and multi-grain boundary cracks would appear in SEM/EBSD imaging (top) before showing the slide with the actual image (below). [Adapted from thesis defense presentation of John Hanson, “The role of grain boundary character in hydrogen embrittlement of nickel-iron superalloys” (2015)]

Each slide should convey a single point

Keep your message streamlined. Make a single point per slide. This gives you control over the pace and logic of the talk and keeps everyone in the audience on the same page.

The slide’s title should be the slide’s main takeaway. In other words, the audience should be able to follow your story just by reading the slide titles. Even if you completely forget what a slide is about, you can just read the title to convey most of what you had to for that slide.

| Context in presentation | Weak title | Strong title | Why? |

| Background slide | “OpenMC” | “OpenMC provides statistical uncertainty on simulation results” | It highlights the most relevant point that motivates your work. |

| Data slide | “Effect on Elasticity” | “Radiation-induced void swelling decreases elasticity” | It states the finding rather than the method. |

| Conclusions slide | “Conclusions” | Whatever the main conclusion was | You said “In conclusion” with your words, tone, and body language. There’s no need to repeat it. |

Strong titles tell a message. Strong titles tend to be full sentences, since you need a full sentence to tell a message. Weak titles tend to be nouns like “Background” or “Boiling Models.”

Here’s one way to figure out what your slide’s title should be: have a friend look at it and say, “I don’t understand what the point of this slide is.” If you find yourself saying, “Well, the thing I’m trying to convey with this slide is X,” then X should be the slide’s title.

If a slide makes multiple points, try one of the following:

- Remove points that don’t come up later in the talk.

- Make multiple slides, each with their own message, title, and content.

- Make parts of the slide appear and disappear to display different pieces of content that together support the title’s message.

Emphasize visuals over text

When you put up a new slide, most people in the audience will stop listening to you and start reading the words on the slide. Most people simply won’t hear what you’re saying. The more words on the slide, the less control you have over what your audience pays attention to. If you’re reading lots of words off the slide, you’ve lost the audience’s attention.

In the best case, a slide has only one complete sentence on it: the title. It’s OK to use terse statements to support and highlight secondary conclusions that aren’t already conveyed by the title. If you have a block of text on your slide, try one of the following:

- Replace the text with a picture

- Break up the slide’s content into multiple slides that each make one point

- Take the text off the slide and put it into your presenter notes

Replace blocks of text with easy-to-read pictures. The original slide (top) describes a procedure in great detail, utilizing multiple long sentences to explain the process. The improved slide (bottom) conveys some of the same information, but with a picture of the measurement apparatus instead of words. The labeling of components serves as supporting text, while the block of text in the top slide is a script for the presenter to read. [Adapted from: R. Scott Kemp, Areg Danagoulian, Ruaridh R. Macdonald, and Jayson R. Vavrek. “Physical cryptographic verification of nuclear warheads.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, no. 31 (August 2016): 8618-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1603916113.]

Make each figure as simple as possible while still conveying its message

The purpose of a figure is to convey a message using visual evidence as support. Your audience usually gives you the benefit of the doubt and assumes that whatever you show in the figure is important for them to understand. If you show detailed data, your audience will get distracted by these details and miss the forest for the trees.

A figure that’s effective in a presentation is usually not the one that came straight out of MATLAB or the one that you made for a paper. Unlike when you’re reading an academic paper or scrutinizing your own data, your audience doesn’t have a long time to pore over the figure. To make the figure more effective, ask yourself what minimum number of things need to be shown for the figure to make its point. Remove details that don’t help prove the point. Simplify data labels, and add emphasis using colors, arrows, or labels.

Simplify labels and add emphasis. The figure in the publication (top) is very exacting: it shows the values for current density and applied magnetic field for many different superconductors. An adaptation of that figure for a slideshow (bottom) leaves off many of the specifics while still communicating the major points. [Adapted from P. J. Lee, “A comparison of superconductor critical currents” (Apr 2014). http://fs.magnet.fsu.edu/~lee/plot/plot.htm]

Avoid jargon, both textual and visual

One way to help your audience understand you is to avoid jargon. Discuss the concepts in terms that anyone in the audience could understand.

Usually “jargon” refers to certain kinds of words, but a picture can be worth a thousand words of jargon. If you show your audience some kind of detail—for example, the exact design of the irradiation facility you are using in your experiment—then they will think that they need to understand that detail. Try to separate the things you needed to understand in order to make the experiment work from the things your audience needs to understand in order to follow your conclusions.

Prepare for the talking part of the talk

It’s tempting to spend all your time preparing for a presentation by working on the slides, but the slides are only a visual aid for the presentation. The point of a presentation is to have a presenter! Otherwise you could just make beautiful slides, print them out, and have the audience read them.

Keep your credibility and the audience’s attention by avoiding technical and procedural problems. Make sure that you can get the projector turned on, that your computer will show the slides, that you have your favorite slide clicker, that the slides look good under this lighting, etc. Try to get to the presentation venue the day before. Figure out where you’ll stand, how to get your computer and the project synched up, and so on.

When actually presenting, stand still, face the audience, and keep gestures to a minimum. Laser pointers are distracting and hard to use. It’s better to make the important parts of the slide stand out on their own. Never turn your back to the audience. If you have clean, simple slides, this should happen automatically. Remember: this talk is about you and your audience, not about the slides.

Before presenting, prepare for the question and answer part of the talk. Figure out what questions you are likely to get and prepare yourself to answer them. Prepare backup slides that are more technical that address a specific point. When you hear a question, wait patiently until the questioner has finished speaking. Then repeat the question and take a breath before answering. This timing will allow other audience members to understand the question and will give you some time to formulate a cogent, coherent response.