Your paper’s Introduction section should provide your readers with the information they need to grasp, appreciate, and build on the knowledge you present. Despite audience-dependent variations, the Introduction generally follows a four-part structure that sets the stage for the core of the paper. Check out annotated examples at the end to see how different authors have introduced their work.

| Contents |

| 1. Before your start 1.1. Identify your purpose 1.2. Analyze your audience 2. Writing your Introduction 2.1. General background: A broad opening 2.2. Specific background: Work done so far 2.3. Knowledge gap: Motivation for your work 2.4. Aim of your paper 3. Quick tips 4. Annotated examples |

1. Before you start

1.1. Identify your purpose

The Introduction provides your audience with the background information necessary to understand the work you’re presenting in the article, and the reasons why you conducted your work. Therefore, clarify for yourself what problem you’re addressing and why your work is important.

1.2. Analyze your audience

Scientists in your specific field will probably understand your work’s motivation whether they read your Introduction or not. They might even skip the Introduction and focus on the Methods and Results. Outsiders are the people who will benefit most from a well-crafted Introduction. This is an opportunity for you to broaden their background knowledge and close the gap in technical knowledge.

Analyze papers from your target journal and follow the journal’s guidelines. This will inform the appropriate length and breadth for your Introduction, as well as the content needed to help your readers follow along. Let’s say you are writing a paper about CFD simulation in nuclear fission reactor. You can assume that readers of Physics of Fluids are interested in developments in fluid mechanics, but may not know much about reactor design. For other journals such as Nuclear Engineering and Design, readers will be nuclear science insiders.

If you are writing for a general audience, your Introduction will start with some broad, motivating background and fewer technical details. Below are excerpts from two journals articles. Although they describe the same research project, one is intended for a general audience (left) whereas the other is directed at scientists with previous knowledge on the topic (right).

2. Writing your Introduction

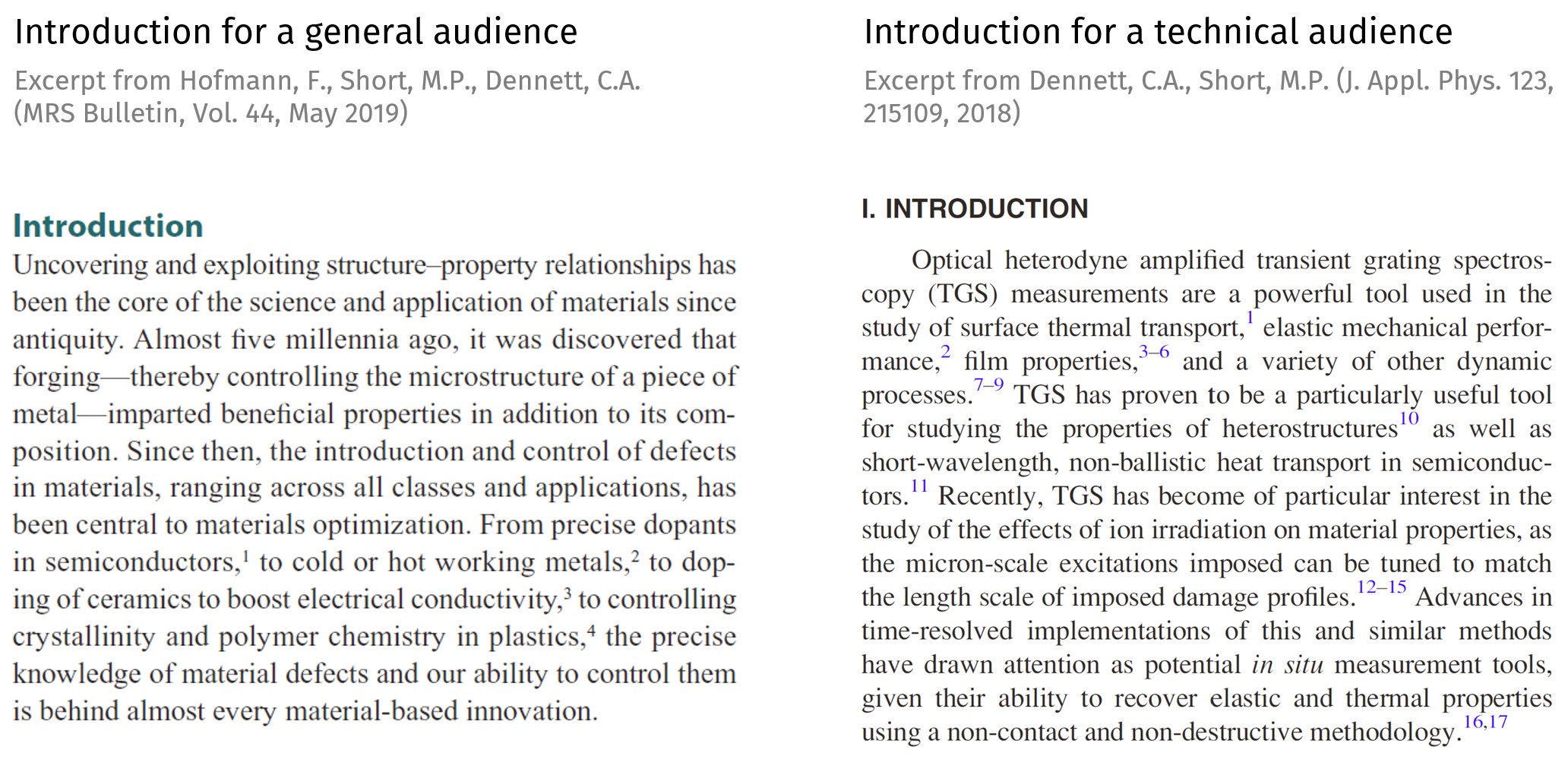

Regardless of length, an effective Introduction resembles the first half of an abstract. Just like an abstract, one way to remember the different components is to visualize an hourglass: start with a broad opening and lead your reader toward the core of your paper.

Here is an example illustrating our four-part structure (see more examples below).

2.1. General background: A broad opening

The general background should demarcate the overall scientific setting of your work. Start with a general topic that everyone in your audience cares about. Note that the general background should give your audience a sense of what to expect from your paper, not an overview of the history of a field. Introduce only necessary background that is related to your work, and make sure it can narrow down to your thesis.

2.2. Specific background: Work done so far

Give your reader a sense of previous accomplishments, current contradictions, and competing theories in the field. Cite previous work that illustrates your narrative and gives a balanced description of the scientific landscape on this research topic.

2.3. Knowledge gap: Motivation for your work

Give evidence of the incompleteness of the current understanding and of the value of investigating the field further. What is the gap that needs to be filled? Demonstrate the importance of this unsolved problem as the motivation for your work.

2.4. Aim of your paper

Finally, clearly state the aim and scope of this article (not the project) and what exact question is answered. You may also briefly explain how the study was conducted, and share a preview of your findings.

3. Quick tips

- Select your target journal carefully. Make sure there is a clear match between your objective for the paper, and the journal’s mission, scope, and readership. This will not only help you write your Introduction but also increase your chances of getting your submission accepted.

- Follow the publisher’s guidelines and read other papers from your target journal to make sure you understand their expectations.

- Only cite relevant work. The previous findings and studies you cite must be strongly related to your research topic, and lead to the knowledge gap of your paper.

- Have a clear story line before writing your Introduction. A paper may be divided into discrete sections but these must all work together. The story you choose for the Results and Discussion sections will determine which theories and past research or methodologies need to be presented in the Introduction. Do not spend excessive amounts of time perfecting the Introduction until you have clear path for the whole paper

- Refer back to your Introduction when you write your Conclusion. The Introduction and Conclusion together serve as “book covers.” Just as your Introduction describes the scientific landscape surrounding your work, your Conclusion will address how your work adds to the field.

4. Annotated examples

|

|

|

To get started or receive feedback on your draft, make an appointment with us. We’d love to help!